The predilection for More Trade

I do not consider an increase in inter-country trade a good thing in and of itself, though that view is common among economists and in the media. For most economists increased trade reflects a putative more efficient international allocation of resources derivative from competition on a global scale. For the media, the enthusiasm frequently involves trade’s alleged employment generating effects, derivative from mercantilism and associated with assessing trade deficits as a prima facie problem of a country “living beyond its means”. Slightly more sophisticated is Adam Smith’s “vent for surplus” that sees trade as the outlet for what cannot be sold domestically.

Rarely noted is that free trade theory is consistent with a decline in bilateral trade due to the likely possibility of different demand preferences between countries and, more esoteric, re-switching of techniques. Except in technical articles one tends to find the blanket generalization that liberalising trade increases bilateral and multilateral flows and that is unambiguously a good outcome. In that context I look at EU trade patterns since the euro’s use became generalized in the early 2000s.

A common currency for the European Economic Community, seriously discussed when the Cold War divided the continent, was part of a broad and deep political process to forge unity in Western Europe. However, in the early concept of a common currency, in the Treaty on European Union (1993, also known at the Maastricht Treaty) its specification is clearly economic, part of the commitment to “sustainable development of Europe based on balanced economic growth and price stability, a highly competitive social market economy” (Article 3, Section 2). As Jeremy Smith and I have argued, the reasonable interpretation of “highly competitive” is that it implies being export competitive.

Whether or not EU policy as implied by the treaties increased export competitiveness, there are obvious reasons to expect the introduction of the euro to facilitate trade among its users, now almost twenty countries. First among these is lower transactions costs in trade among euro users, which in itself could reflect trade “diversion” not greater efficiency.

The Mysterious Switch

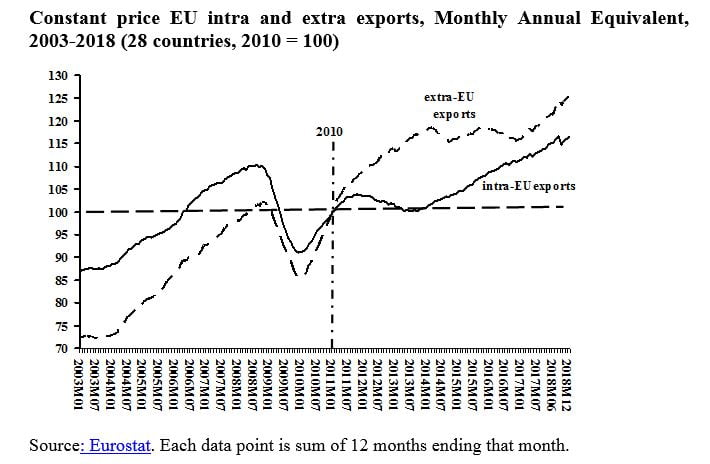

The chart below shows an index of exports of all EU member countries in constant prices, among themselves and as a group with non-EU countries. At the end of the time period, euro users included 19 countries and nine non-users, with the former accounting for slightly less than eighty percent of intra-EU trade in 2018. All the largest trading countries used the euro except for the United Kingdom. Prior to the Great Crash of 2008-2010, the two trade categories behaved as expected. Intra-EU trade increased by substantially more than trade with non-members before 2008, as the transactions cost effect would predict.

However, after 2010 the two categories reverse, with extra-EU exports increasing by substantially more than intra-exports. For 2018 as a whole, extra-EU exports rose 26% compared to 2010, while intra-exports increased by 16%. After 2010 other influences overwhelmed any common currency transaction gains.

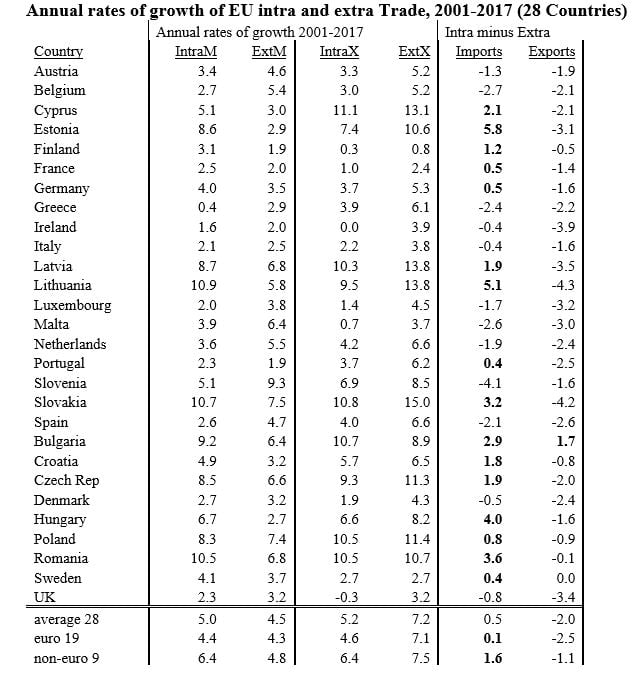

If we begin with the lowest point in late 2009, the growth of extra-EU exports from the 28 countries increased by substantially more than for exports among themselves, 47% compared to 28%. These numbers suggest that the extra-EU export demand was strong enough to overwhelm common currency benefits to trade. European Commission fiscal austerity policies provide a possible reason for weaker intra-EU export demand. Country level trade statistics allow a closer look at that possibility.

2 responses

best text for a better europe

Thank for your best text for a better europe