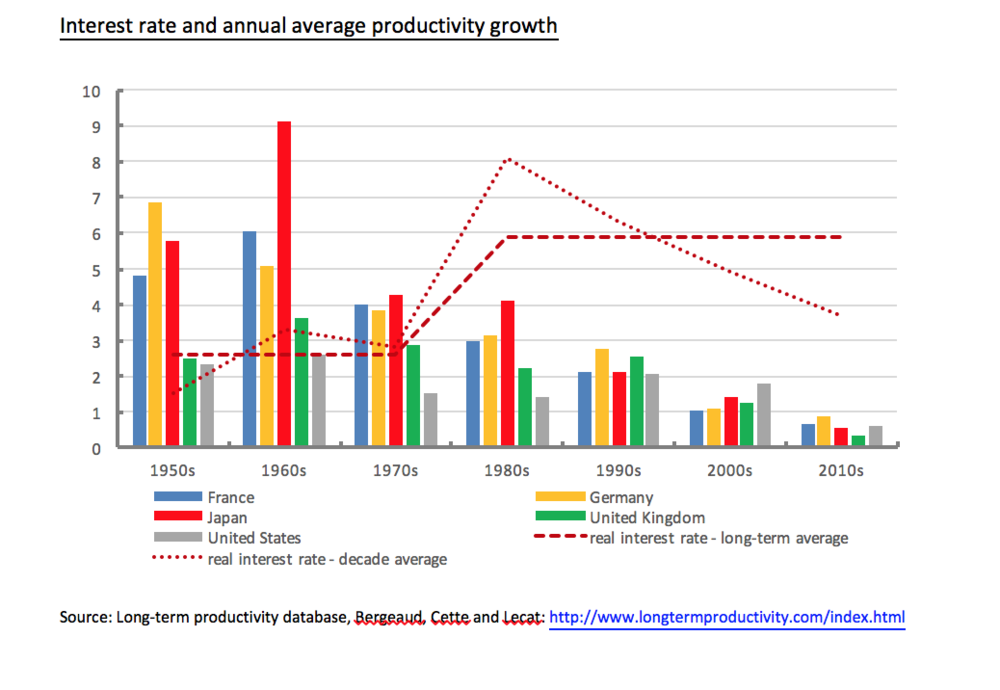

And then the relation between interest rates and outcomes: low interest rates through the golden age coincided with unprecedentedly high growth. The reversion to high rates coincided with a progressive decline in growth.

Interest rate and annual average productivity growth

This should hardly be a surprise. When it comes to conventional monetary policy, cuts in rates are aimed at fostering higher growth. Low interest rates make borrowing cheaper and should encourage entrepreneurs to expand activity (as well as encouraging consumers to spend). But mainstream economics takes a different approach to long-term rates, which are somehow dictated by events rather than dictating events. These simple figures show the mainstream analysis is contradicted by reality.

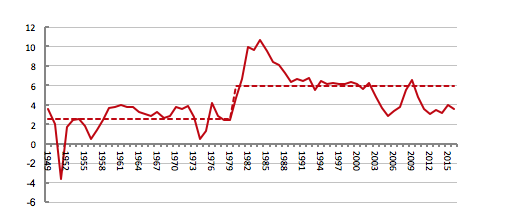

Moreover the conventional narrative around long-term rates has been inconsistent throughout. In the 1970s calls for the liberalisation of capital were aimed at increasing the availability of savings which would drive interest rates lower and foster higher growth. A decade later the IMF recognised that rates had been very high:

These measures imply that real interest rates in the major industrial countries during the 1980s have been significantly higher than those that prevailed in the 1950s and early 1960s and even further above those of the 1970s. (IMF,

World Economic Outlook, 1985)

Later in 1999 Christopher Allsopp and Andrew Glynn (

‘The Assessment: Real Interest Rates’,

Oxford Review of Economic Policy

, 15 (2), Summer, 1–16

) observed:

There is a widespread impression that real interest rates have been very high since 1980 in comparison with post-Second-World-War experience. The data … confirm that this is indeed the case.

So this view of high rates to at least the end of 1999 overlaps by around 15 years with the present idea that rates have been in decline for 30 years.

In reality low rates of interest were deliberately engineered by the architects of post-war policy (successfully) to support aggregate demand, output and employment. Financial liberalisation removed the restraints on capital that had supported relatively low interest rates for C20Q3, and were exacerbated by the ‘Volker shock’ (i.e. sharp increases in the central bank policy rate) and overfunding of government debt (i.e. forcing more long-dated debt onto the market than the market wanted).

To the extent that rate were lower from the start of C21, this followed a vast expansion of the global money supply as all restraints on finance were removed in the wake of the dot.com crash. Since the GFC, central banks have had to open up their balance sheets to take up the slack.

These policy actions have taken place in desperation given the progressive decline in growth and global financial instability that were the consequences of high rates.

Moreover, even to the extent that interest rates are genuinely cheap, they are not sufficient given the collapse of business confidence amidst public retrenchment and private debt overhang. This should hardly be a revelation. Strictly (in Keynes’s scheme) this is not a liquidity trap, but a collapse in the marginal efficiency of capital that reflects the animal spirits of firms. However, the immediate policy need is one and the same: a material increase in government spending to revive demand and business confidence. The more challenging ask is to renew a global system that will foster permanently low interest rates on a sustainable basis.

The argument here mirrors exactly those of the 1920s and 1930s: whether economic dysfunction is rooted in the real side of the economy or in the monetary system. The difference this time around is that monetary argument is barely heard, if even acknowledged to exist at all. The point I am keen to make today is that subsequent experience showed the real argument does not even stand up in its own terms.

Footnote

[1]

E.g. Ben Broadbent, ‘The distributional implications of low structural interest rates and some remarks about monetary policy trade-offs’, speech 18 November 2016.

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/speeches/2016/speech940.pdf

P.S. Due to an error in the original posting this blog was amended at 17.18 on 23 December, 2016, to include a missing paragraph (between the charts) and heading.

2 responses

Warren Mosler advocates a permanent zero rate of interest. Quite right.

If you took the rate to 1985, and measured the average in the 30 years prior, and then took the average for the 30 year period after 1985, you would get a different result, showing the average for the 30 years after 1985 to be lower than the preceding thirty years.

The rate of interest, as Marx showed (and before him Hume and Massey) is determined by the demand and supply for money-capital. I am talking about the real rate of interest here, in the market, not the meaningless official interest rates, such as the Bank Rate, or the heavily manipulated yields on government bonds.

Interest rates fell from the mid 1980’s, for the simple reason that globally the rate of profit rose massively. Productivity rose, wages fell, the rate of surplus value rose, and the value of constant capital (fixed capital plus materials) dropped sharply. Existing fixed capital suffered a significant moral depreciation due to new technology which made existing machines obsolete, and massively reduced the cost of producing the new machines that replaced it. As global growth slowed, the prices of raw materials dropped, and new more efficient ways of obtaining and using those materials were developed.

For example, the consumption of oil increased by just a seventh of the rise in global GDP from the 1980’s to the early 2000’s. The supply of new money-capital arises from realised profits (plus some small additions from mobilising existing stocks of money-capital, and money used for other purposes). During the period after the mid 1980’s this supply of new money-capital from realised profits rose much faster than the demand for additional money-capital, so global interest rates fell through the period.

But, its also wrong to say that the purpose of monetary policy is to reduce interest rates and thereby stimulate economic activity. As interest rates dropped, so it led to an astronomical rise in the capitalised value of revenue producing assets. The Dow Jones rose by 1300% from 1980 to 2000, compared with just a 250% rise in US GDP, and this pattern was matched in other stock indices in the US and across the globe. Bond prices went into a huge bubble, and land and property prices went with it.

But, the result was that eventually, the owners of these revenue producing assets increasingly lost interest in the small amounts of revenue that they produced, and became transfixed with the paper capital gains that these assets seemed to produce year after year. So, for example, pension funds started to believe they could finance future pensions out of the capital gains rather than the revenue produced by the assets, which led employers in the 90’s to take pension holidays from contributions and led to no increases in workers contributions to their pensions in parallel with the higher prices of the bonds and shares they needed to buy to provide the capital base of their future pension income. It led to the pension black holes seen today.

A look at London property shows large numbers of such speculators who buy property, which they intentionally leave empty, because they are not interested in the 5% rental yield they might obtain, when instead they expect to make a 10-20% capital gain on the property year after year, as low interest rates, and money printing pumped into the banks to finance cheap mortgages year after year inflates the property price, just as it inflates the prices of shares, and bonds.

At this point, with nearly all of the wealth of the top 0.001% n the form of these paper assets, and property the aim of monetary policy, at least in the last ten to twenty years, has been to keep those asset prices inflated, at whatever cost, including the cost of destroying real capital and productive capacity. That is why the authorities have been at pains to protect the banks, to bail them out with billions of dollars, and to nationalise them if required – as currently being seen in Italy.

The monetary policy has actually damaged real productivity capacity and growth, because it discourages real productive investment, which continues to carry risks, and encourages instead financial speculation in property, stocks and bonds, which appears to have no risks, given the underpinning of the authorities, and yet still produces huge capital gains. It has drained potential money-capital from productive investment, slowing growth, and it has drained money from circulation in the consumption of commodities, thereby causing a deflation of consumer goods prices, because anyone with any amount of spare cash has used it to become a buy-to-let landlord or some other kind of financial speculator. That was made worse by the imposition of policies of austerity, which most certainly were not intended to stimulate economic growth.

Fortunately, that self-destructive process has reached its limits, as even the central banks and financiers seem to have realised. Financial bubbles also burst more quickly and violently than they are inflated – as 2008 gave a foretaste of – and as those bubbles burst, the money-capital will find a home in productive investment instead, and will begin to circulate commodities.