The Taylor “Review of Modern Working Practices”, published on Tuesday, is a fundamentally complacent document:

“National labour markets have strengths and weaknesses and involve trade-offs between different goals but the British way is rightly seen internationally as largely successful.”

True, the report expresses a number of reasonable aspirations and contains a number of sensible but gentle proposals, but it fails to come up with any strong proposals for dealing with the real problems faced by insecure workers in the UK today. It does not even make the obvious recommendation, to remove the big court fees now imposed on workers wishing to challenge their employer in an industrial tribunal. And while noting that the UK labour market suffers from weaknesses such as real wage growth and productivity, it fails to explain that these are the necessary logical results of the model, and not aberrations.

Real wages falling heavily again

Publication of the Taylor Review was followed on Wednesday by the latest monthly employment stats from the Office for National Statistics (ONS). These tell us that the number of those in work continues to rise significantly, but that real wages are falling at their fastest rate for nearly 3 years. Indeed, if we take the period since the Conservative government took office 7 years ago in May 2010, we see that real wages have fallen on an annual basis for 52 months out of a total of 84 months (Tale 16, dataset A01). Average total real weekly pay (at constant 2015 prices) was £493 in May 2010, and is £487 in May 2017 – a level it first reached in August 2005.

False claims by the CBI for “flexible labour markets”

Yet despite these long-running abysmal pay statistics, the Taylor report gives prominence to claims from the Confederation of British Industry (CBI) that are simply not true. Take this example :

“The UK’s flexible labour market has been an invaluable strength of our economy, underpinning job creation, business investment and our competitiveness. These strengths cannot be taken for granted, so it is essential that flexibility is retained and enhanced.”

The “flexible labour market” has certainly not underpinned business investment, which – having improved in 2015 – fell back in 2016. In fact, since the start of the 21st century, business investment has grown by around 1% per year, which after allowing for population growth, means almost no increase per head at all. The contrary case is far more plausible – that our excessively flexible labour market encourages the substitution of labour for capital and leads to low levels of investment.

The UK is (with Italy, among “advanced economies”) at the bottom of the international chart for investment as a percentage of GDP, where we have long languished. Nor has labour flexibility underpinned an improvement in “competitiveness”, if we take our continuing large trade deficit as strong evidence.

But the false claim by the CBI I want to look at in more detail relates again to real wages. The CBI’s evidence to the Taylor Review claims:

“Flexible labour markets tend to enjoy higher employment rates and lower unemployment than those with more rigid approaches and – as CBI research from 2014 shows – over many decades, they have better protected the labour share and delivered more real terms wage growth than more rigid systems. This is why flexibility matters.” (My emphasis).

So the claim is that over many decades, it is “flexible labour markets” which have delivered more real terms wage growth than more rigid systems…

This even fails to do justice to the CBI’s own work on the subject. Their 2014 report, “A better off Britain: Improving lives by making growth work for everyone” simply states:

“Pay has risen faster than the cost of living throughout most of the last 50 years – and between 1990 and 2008 pay grew faster in the UK than in any other advanced economy”.

I have no reason to doubt this statement for the period to 2008 – but (a) Britain did not have what is now called a “flexible labour market” for the first big part of the 50 years, (b) real wages slowed dramatically once we did have a flexible labour market, and (c) since 2007, the UK’s real wages have fallen heavily – precisely due to our flexible labour market!

How real pay in the UK has crashed compared to other countries

Geoff Tily gave this chart from OECD data in his Touchstone blog in 2016, showing a fall over the previous 8 years of 10% in the average UK hourly wage – next to Greece, by far the worst in class:

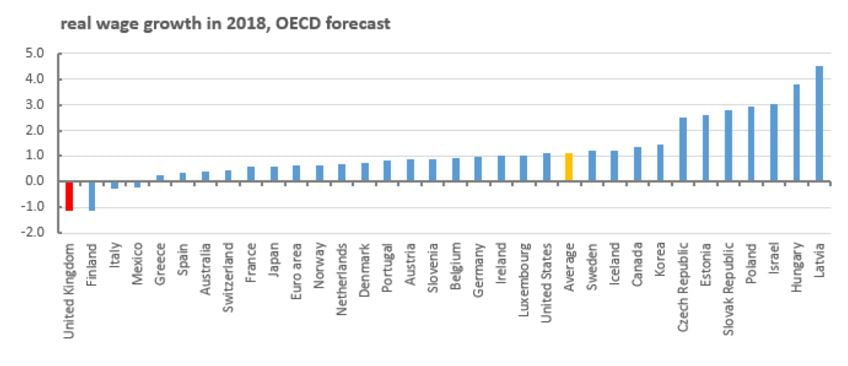

After a couple of years of minor growth in real pay, we are sliding back again, and the OECD sees this continuing into next year – unlike almost all comparator countries: (chart also from Tily, Touchstone blog, 7 June 2017):