What is deflation? What has caused inflation to fall? And why is there no such thing as ‘good deflation’?

Introduction

On Monday the Office of National Statistics (ONS) announced that inflation at 0.5% was lower than the 1% rise that had been predicted by the Bank of England as recently as November. And it was lower than the prediction of most economists who believed prices would rise by to 0.7%.

We at PRIME are not surprised, as we have tracked Britain’s disinflation (falling prices) for some time. And we warned as far back as 2003, and again in 2006, 2010, and e.g. in October, 2014 of the threat of global debt-deflation. Because policy-makers lack the tools to correct a deflationary spiral, the prospect of deflation is frightening.

We therefore find ourselves at odds with the British Chancellor, George Osborne who announced that the fall in inflation to 0.5% was “welcome news”; with the Bundesbank President, Jens Weidmann, who argued recently that “an inflation rate that for a few months lies below zero, for me, doesn’t represent deflation”; and finally with the Financial Times which ran the following headline on the news of Britain’s low inflation rate: ‘Good deflation’ seen as spur to growth”. (Note: this headline appeared in the paper edition of 14 January, 2015, and not in the digital edition.)

For ordinary consumers, workers, farmers and for the owners of firms and shops – especially those with debts – there is no such thing as “good deflation”.

What is deflation?

Deflation occurs when prices (not necessarily all prices, but the average price level) fall below the costs of production – i.e. when prices become negative. So in a deflationary environment producers will sell a good or service at below the level of profitability or below the cost of making that product. They will do this just simply to get products off the shelves and out of the warehouse – before prices fall even further.

Deflating prices may appeal to the consumer, and may boost consumption in the short-term, but they are associated with savage costs that will quickly catch up with British and European, and potentially even American consumers.

The reason is as follows: if producers or retailers sell their wares below cost, then they will invariably make a loss on those sales. Their business will become less profitable. The sensible response when a firm is not able to price its goods to make a profit, or to cover costs, is to produce less of what it is unprofitable. In other words: to shrink productive activity. This is done by cutting production, trimming wages and inevitably, laying off staff. Thus the fall in prices, leads to a fall in profits, which leads to falls in wages and to a rise in unemployment. Unemployment means that workers lack disposable income, and find it harder to buy products and services on offer. As a result producers sell even fewer of their already low- priced products or services. Bankruptcies and unemployment rise, while wages and prices fall further, and so the deflationary spiral takes hold.

Furthermore, the price indices managed by government –in particular the Consumer Price Index (CPI – are used to fix wages in private and public sector wage negotiations. Benefits received by disabled people and pensioners increase (or decrease) in line with CPI inflation. So when the CPI falls, be sure wages and benefits will fall too. (And with a political consensus in the British Parliament promising savage spending cuts in the next Parliament, pensions and other benefits will have to be cut in line with the falling level of CPI, if the proposed extreme spending targets are to be met.)

For whom is deflation good?

Deflation is good for those on fixed incomes, as these will rise in real terms as prices fall.

Deflation is good for creditors/money-lenders or the rentier class. This is because while prices can fall below zero, interest rates cannot. So while wages or incomes may fall below zero, interest rates (at what is known as the ‘zero-bound’) will rise relative to these falls. If prices fall below zero, say to minus 2% but the interest rate remains at plus 2%, then the real rate of interest rises to 4% in a deflationary environment.

And while prices, wages and incomes can fall below zero, debts remain fixed, and in relation to falling wages and incomes – rise in value.

This is why creditors encourage, and even pressure politicians and policy-makers (central bankers and officials) to apply deflationary policies – because deflationary policies protect and even increase the value of their most important asset – debt.

To repeat: whereas inflation erodes the value of debt, deflation increases the real value of debt.

So in a deflationary environment, creditors (effortlessly) grow richer as the value of debts owed to them rises (until their debtors default); and debtors with falling incomes find their debts become unpayable.

Keynes once wrote that:

“Deflation…involves a transference of wealth from the rest of the community to the rentier class and to all holders of titles to money; just as inflation involves the opposite. In particular it involves a transference from all borrowers, that is to say from traders, manufacturers, and farmers, to lenders, from the active to the inactive…Modern business, being carried on largely with borrowed money, must necessarily be brought to a standstill by such a process.” [1]

So no, Chancellor, 0.5% inflation is not “welcome news”.

What causes deflation?

In an economy that has high and still rising levels of private debt – owed by individuals, households, SMEs, big companies, banks and other financial institutions – deflation can be caused by borrowers paying down debts. If there is a crisis, as in 2007-9; and if prices, profits and incomes are falling, debtors become wary, and begin to use available income to pay off their debts. This deleveraging of debt, if combined with falling real incomes (as in the UK and much of the Eurozone) causes deflation, because it contracts the amount of money in the economy that can be used to purchase goods and services. As producers and suppliers compete to attract sales from penny-pinching debtors, they lower prices. We see this happening in the supermarket sector, where cut-price stores are out-competing mid-range stores – a cut-throat process aimed at luring in shoppers, but that may leave very few standing.

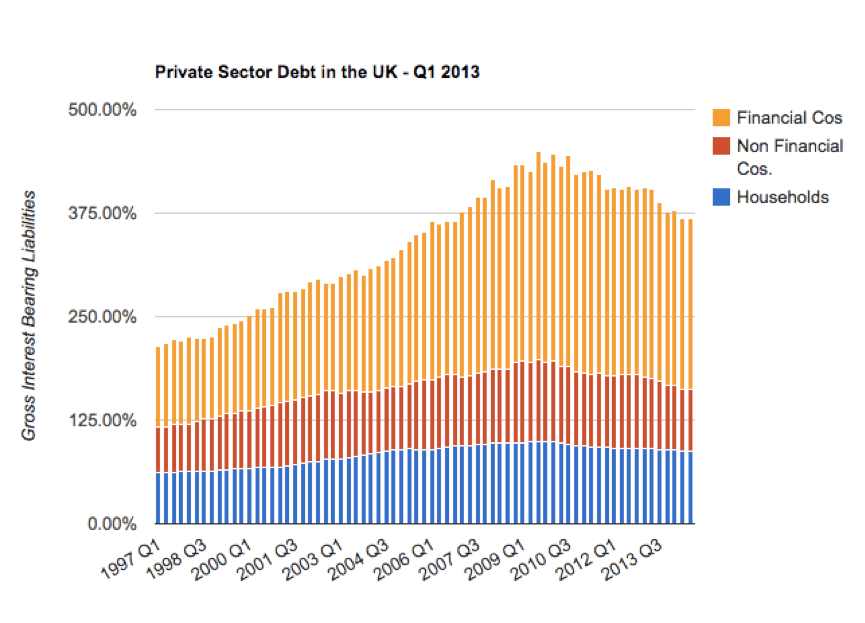

Britain’s private sector has very high levels of debt as the chart below shows – amounting to almost 370% of national income, or GDP.

Source: UK Private Debt Levels, Qtr 3, 2014 by Neil Wilson, http://www.3spoken.co.uk/

6 responses

"Deflation occurs when prices (not necessarily all prices, but the average price level) fall below the costs of production – i.e. when prices become negative."

This reads like something Caitlyn Upton said.

http://mic.com/articles/49187/6-worst-beauty-pageant-responses-in-the-history-of-miss-america#.NbGc8VJo9

Wow. This article is total CRAP.

Mark Carney was not appointed to the BoE until November 2012.

Is deflation necessarily defined as prices below the cost of production? I understood it as falling prices, which doesn’t necessarily lead to the same thing. It’s still bad, I’ll agree with you there, but it only gets really bad if it’s prolonged and expected, no?

Falling prices are known as disinflation…deflation is when prices become negative. …Mmy point is that the direction of travel is very clearly downward…global pressures from China through Europe and even the US are adding to downward pressures on UK prices…

And no, they’re not only bad when prolonged, and no, they are never expected…

Nope,

Disinflation is a decrease in the rate of inflation.

Prices cannot become negative unless the seller pays someone to take the goods.

Falling prices are not always bad. What about the economies of scale?

Falling prices are expected in technological advances.