On 14th October, Mr Osborne’s new version of the Charter for Budget Responsibility falls to be discussed by the House of Commons. The headlines he seeks will be about “entrenching” a policy of permanent budget surpluses in “normal times”, to bind all future governments – especially Labour governments!

But – reminding us of St Augustine’s prayer, “Lord, make me chaste… but not yet” – “normal times” are deferred for a few more years. Mr Osborne ensures that his Charter’s more severe consequences will not bite him during his term of office. This is economics as political theatre, not as serious policy-making.

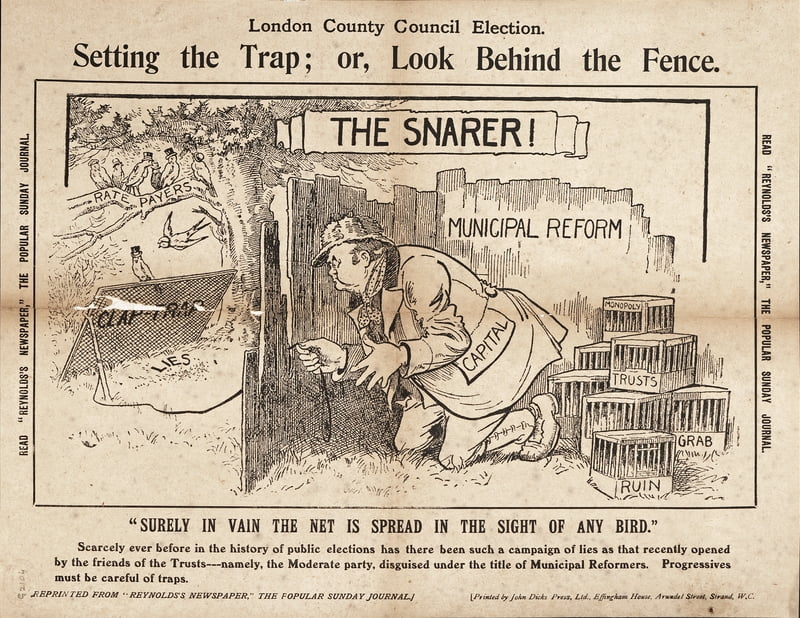

In his speech to the Labour Party conference, Shadow Chancellor John McDonnell rightly described the new Charter as just “a political stunt” and a “trap [set] for us to fall into.” He did not however indicate how the Labour Opposition should deal with it. We argue that Labour must avoid the trap.

The economy can be influenced by the full range of government policies, but nowhere can governments, by Canute-like injunction, force the waters of economic activity to ebb or flow with precision at his command. No Chancellor can actually control the level of a budget deficit, since government revenues depend so critically on revenues from employment, the state of the economy, and in particular the health of the private sector.

Labour should contest the Osborne narrowly obsessive “deficit” narrative, by focusing on the wider set of economic objectives – including of course good financial management – that are required to renew our economy and help Britain prepare well for an uncertain future.

While initially letting it be known, via huge media leaking, that he wanted to enforce mandatory budget surpluses by new legislation (see below for more on this), in the end the Chancellor is simply replacing the Coalition’s Charter (updated in December 2014) with a new one, made under the Budget Responsibility and National Audit Act of 2011.

The 2011 Act simply requires the government to draft a “Charter for Budget Responsibility” which must include

- The Treasury’s objectives in relation to fiscal policy and policy for the management of the National Debt

- The means by which the Treasury’s objectives in relation to fiscal policy will be obtained (the “fiscal mandate”), and

- Matters to be included in a Financial Statement and Budget Report

The objectives and “mandate” can be as narrow or broad as the House of Commons is willing to support – and that surely means proposing to broaden them to cover the policy goals Labour aims to achieve, and to which fiscal policy is relevant. For fiscal policy – which is not defined in the Act – can and should not be seen as limited to “tax and spend” in a narrow sense, but as supporting a holistic economic framework. An economy working at full capacity hugely helps with the achievement and maintenance of sustainable public finances.

We envisage Labour setting out its own outline of the objectives and mandate it wants to pursue, to be included in an Opposition amendment to the motion to adopt the current draft Charter. In this way, it can avoid being kidnapped and constrained in a tiny prison entitled “deficits and debt” through articulating a broader vision of society and the economy, while at the same time affirming the commitment to good financial and fiscal management.

In this spirit, we have drafted a set of Objectives and “Fiscal mandate” which correspond, as we understand them, to the broad goals and approaches outlined by Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell, as Leader and Shadow Chancellor respectively. We offer these proposed objectives and draft mandate for consideration by parliamentarians:

Treasury objectives in relation to fiscal policy and the national debt

- To promote employment and economic activity at its fullest level, consistent with achieving the defined inflation target over the medium term, and with full and fairly remunerated employment consistent with that target, which assists in generating government revenues

- To work closely with the Bank of England and the Debt Management Office to ensure that the objectives and implementation of fiscal policy are mutually supported and reinforced by monetary and debt management policy

- To work constructively with relevant government departments to rebalance and strengthen the economy for the future, in particular by supporting private sector investment and exports.

- To promote and implement a government-led and supported public and private investment programme that prepares our country for the future, one that includes new housing and infrastructure, that works with the private and third sectors to enhance investment in R & D and other joint initiatives, skills training, and major changes needed to transition towards the post-carbon society

- To achieve a fair, progressive and balanced taxation system to which all contribute their equitable share, so that the public services citizens depend upon can be sustainably financed and developed; a taxation system which targets avoidance and evasion

- Within the means available, to promote a fair and cost-effective policy on social welfare which addresses people’s essential needs, targets any misuse, but wherever appropriate encourages autonomy, employment and economic activity

- To underpin and support the above objectives, to ensure that the public finances are sustainable and well managed in their support of the economy and social fabric

- To progressively reduce public sector net debt as a proportion of GDP.

The “fiscal mandate” (the means by which these objectives are to be achieved) can then be developed, but could for example simply adapt and add positive elements to the mandate of the previous Coalition government:

Fiscal mandate

- A target for annual gross public investment of not less than [5] per cent of GDP by 2019-20, to include [xx] new publicly funded affordable dwellings to be built by the end of that year

- A target to increase current annual revenue from taxation in respect of avoidance and evasion progressively, and by at least [£50 billion] by the end of 2019/20; and through well-paid employment, increased economic activity and a fair, progressive and balanced overall taxation system to annually increase the level of tax revenue to help close the current budget gap.

- To take necessary further steps towards achieving a target for public sector net debt as a percentage of GDP significantly below the 2015-16 level at a fixed date of 2019-20, ensuring the public finances are restored to a sustainable path

- To set a forward-looking target for the achievement of a current budget balance by the end of the rolling, five-year forecast period, provided that targets to be approved by Parliament for levels of employment, inflation and development of GDP – are achieved

Background to the debate on the Charter.

In his recent speech to the Conservative Party Conference, Chancellor George Osborne beat a familiar drum:

We are still spending much more as a country than we raise. In the spending review this Autumn, we’ve got to finish the job…So we’re going to run a surplus. What that means is that in good years, we’ll raise more than we spend and use the money to reduce our debts. That way we’ll be better prepared when the storms come.

Except that when the storms came in 2008-09, they were unconnected to the tiny current budget surplus or modest level of public debt at that time – they were driven by the winds of out-of control private debt and rapacious finance sector greed. Mr Osborne now likes to forget what his first budget report highlighted (Chapter 1):

Between 2002 and 2007 there was a near tripling of UK bank balance sheets and the UK financial system had become one of the most highly leveraged in the world, more so than the US. As a result, the UK was particularly vulnerable to financial instability and was hit hard by the financial crisis.

The deregulation of the finance sector that allowed this to happen was the joint responsibility of Labour and Conservative party leaderships, who had united behind the philosophy of liberalisation.

Mr Osborne’s relentless political attack on the modest Labour pre-crisis deficits ignores another matter. There have been very few years since the 1970s – whichever party is in government – in which there has not been a deficit! A very recent House of Commons Briefing Paper points out that

Over the last six decades budget deficits have been the norm. Since 1955/56 the UK’s public sector budget has been in surplus in only eight years; the last surplus was recorded in 2000/01.

And the OBR tells us (Economic and Fiscal Outlook, July 2015, para. 5.18)

The public sector has run a surplus in only five of the last 40 years – and in four of those that was only because economic activity was running above its sustainable level (at least with the benefit of hindsight). Our central forecast of a structural budget surplus of 0.5 per cent of GDP in 2019-20 and 2020-21 would be the largest in at least 40 years – just topping the 0.4 per cent in 2000-01.

To recall, over the last 40 years, Labour was in government for 17, while for 23 years there were Conservative or Conservative-led governments. Thus the main thrust of Osborne’s propaganda – that deficits are specifically linked to Labour governments – is mendacious, as he well knows.

So when, on 14th October, Mr Osborne’s latest version of the “Charter for Budget Responsibility” is discussed by the House of Commons, with ritual attacks on the Opposition on deficits and debt, we need to underline its character as political theatre, not economic policy-making.

It follows a series of such initiatives since Gordon Brown’s first “Code” in 1999 under which the famous “golden rule” was launched.

Earlier in the year, it was mooted widely in the media that the Chancellor intended to introduce new legislation to require and enforce budget surpluses. The Financial Times, in an editorial, rubbished this proposal, saying

His plan to create a legal requirement for governments to run a budgetary surplus is primarily a piece of political positioning. It will do little to keep the UK’s credit safe.

In his Mansion House Speech in June, and contrary to the press-leaked reports (which he undoubtedly inspired), the Chancellor did not mention legislation, but spoke instead of

the chance to entrench a new settlement that… in normal times, governments of the left as well as the right should run a budget surplus to bear down on debt and prepare for an uncertain future.

In the Budget we will bring forward this strong new fiscal framework to entrench this permanent commitment to that surplus, and the budget responsibility it represents.

“Entrenchment” in the UK constitutional system is almost impossible, but has turned out in this matter to be meaningless. For we now see that this “entrenchment” comes to no more than a quick debate and winning a one-off vote in the House of Commons on a swiftly-replaceable Charter.

So it’s not entrenched at all. Mr Osborne reserves to himself the capacity to change his own mandate almost at will, and also avoids the legislative perils of the House of Lords.

The “new” Charter, as mentioned above, is of precisely the same character as the two previous Charters under the Coalition’s Budget Responsibility and National Audit Act of 2011.

The terms of the Coalition’s 2011 Charter gave the Chancellor a great deal of wriggle room on both its objectives and “mandate”. Its objective was short and broad (and note the references to “wider government policy” and to monetary policy, which our proposal develops):

[to] ensure sustainable public finances that support confidence in the economy, promote intergenerational fairness, and ensure the effectiveness of wider Government policy; and support and improve the effectiveness of monetary policy in stabilising economic fluctuations.

And the 2011 fiscal policy “mandate”:

a forward-looking target to achieve cyclically-adjusted current balance by the end of the rolling, five-year forecast period.

At this time of rapidly rising debt, the Treasury’s mandate for fiscal policy is supplemented by a target for public sector net debt as a percentage of GDP to be falling at a fixed date of 2015-16, ensuring the public finances are restored to a sustainable path.” [Our emphasis]

As we discovered over the last Parliament, the “rolling five-year forecast period” within which the current budget was to be balanced did indeed roll ever onwards, never likely to be achieved, deferred always to some future date. Indeed, the great success of this part of the “mandate” is that government could never, by definition, be in breach of the target!

So what do we find in Mr Osborne’s new version of the draft Charter, to be voted on next week? It’s worth a close look:

Objectives for fiscal policy

3.1 The Treasury’s objectives for fiscal policy are to:

• ensure sustainable public finances that support confidence in the economy, promote intergenerational fairness, and ensure the effectiveness of wider government policy

• support and improve the effectiveness of monetary policy in stabilising economic fluctuations

Not too much to complain of there, given its generality though note the absence of explicit reference to “investment”. And note the continuing references to the linkage of fiscal and monetary policy.

On to the “mandate”:

In normal times, once a headline surplus has been achieved, the Treasury’s mandate for fiscal policy is: a target for a surplus on public sector net borrowing in each subsequent year

For the period outside normal times from 2015-16, the Treasury’s mandate for fiscal policy is: a target for a surplus on public sector net borrowing by the end of 2019-20

For this period until 2019-20, the Treasury’s mandate for fiscal policy is supplemented by:

a target for public sector net debt as a percentage of GDP to be falling in each year

These targets apply unless and until the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) assess, as part of their economic and fiscal forecast, that there is a significant negative shock to the UK. A significant negative shock is defined as real GDP growth of less than 1% on a rolling 4 quarter on-4 quarter basis.

If this “shock” occurs:

..the target for a surplus each year is suspended (regardless of future data revisions). The Treasury must set out a plan to return to surplus. This plan must include appropriate fiscal targets, which will be assessed by the OBR.

Let’s recap. At present, we are not “in normal times” – and indeed for 60 years the UK has hardly ever been “in normal times”. So the first target is to get a surplus on the overall budget (however tiny) by the end of 2019/20, i.e. March 2020 (memo: the General Election is due in May 2020). The overall budget means the total of current and capital spending.

In addition, net debt should be falling as a percentage of GDP in each year till then. (Note that under this part of the mandate, the nominal amount of debt may continue to rise, but if by a smaller percentage than GDP, net debt as a percentage of GDP will still fall).

Once – but only once – a “headline surplus” has been achieved, “normal times” commence. Then, in each year, there should be an overall (current + capital) budget surplus. That is, from then on there can be no net borrowing for capital investment purposes.

There is however no target for the amount of surplus to be achieved (one pound sterling per year would suffice), so the amount by which debt is to be “paid down” (if at all) may be negligible. There is no reference in the Charter to balancing the overall budget over any business cycle.

And if ever the Office for Budget Responsibility considers that GDP annual “growth” is, or has just been, or will be, below 1% (as was virtually the case in 2012), then all bets are off – the targets are suspended.

But there is another “mandate” in the new (and December 2014) version of the Charter which was not in the 2011 Coalition version – the “welfare cap”, expressed as

the cap on welfare spending, at a level set out by the Treasury in the most recently published Budget report, over the rolling 5-year forecast period, to ensure that expenditure on welfare is contained within a predetermined ceiling” [page8].

The cap does not apply to all benefits – in particular, Job Seekers’ Allowance and its “passported housing benefit” are excluded from it, so that if there is another deep recession, spending on specific benefits for the unemployed will not be restricted by the cap. Old age pensions are likewise excluded (inter-generational fairness, anyone?).

A modern history of Fiscal Codes and Charters

We have mentioned that the first such initiative – “the Code for Fiscal Stability” – was invented during Gordon Brown’s Chancellorship in 1998. The Finance Act of that year provided its legal base (section 155). That Code contented itself with laying down the general apple-pie principles to be applied – transparency, stability, efficiency etc. – while requiring the government to

state and explain its fiscal policy objectives and the rules by which it intends to operate fiscal policy over the life of the Parliament.

The Code enabled the government to change its objectives and rules, if it gave reasons for so doing.

Prior to the financial crash of 2008/09, the key rules were encapsulated in two “rules” set for itself by the government under, but not in, the Code:

The golden rule: over the economic cycle, the Government will borrow only to invest and not to fund current spending

the sustainable investment rule: public sector net debt as a proportion of GDP will be held over the economic cycle at a stable and prudent level.

The fiscal rules provide benchmarks against which the performance of fiscal policy can be judged. The Government will meet the golden rule if, on average over a complete economic cycle, the current budget is in balance or surplus. The Chancellor has stated that, other things equal, net debt will be maintained below 40% of GDP over the current economic cycle, in accordance with the sustainable investment rule.

Taking the period of the Labour government to 2007/08, the investment rule was adhered to – the debt to GDP ratio stayed well below 40%. As for the golden rule, it was mildly breached: the current budget deficit before the crisis was on average about 0.1% per annum – a minimal departure, in itself of no macroeconomic consequence.

More worrying was the fact that net investment was less than 1.5% of GDP per year – a serious under-investment (in part due to the damaging fixation with PFI contracts which were not counted as public investment).

Once the crash came, the golden rule had to be jettisoned. Government expenditure on the “automatic stabilisers” (unemployment benefits etc.) necessarily leapt, while government revenues fell sharply. An investment stimulus was rightly (if inadequately) introduced, with net investment doubling to 3.4% of GDP and helping the economy to grow again in 2010. The current budget deficit, as had happened in the recession of the early 1990s under the Conservative government, also grew sharply – as therefore did the overall budget deficit.

But in an unfortunate political precedent, the Labour government in early 2010 – a few weeks before the General Election – passed the Fiscal Responsibility Act 2010 which sought to impose fiscal rules and targets via primary legislation. Section 1 included the following Canute-like [1] injunctions :

(1) The Treasury must ensure that, for each of the financial years ending in 2011 to 2016, public sector net borrowing [as a % of GDP] is less than it was for the preceding financial year.

(2) The Treasury must ensure that, for the financial year ending in 2014, public sector net borrowing [as a % of GDP] is no more than half of what it was for the financial year ending in 2010.

(3) The Treasury must ensure that (a) public sector net debt as at the end of the financial year ending in 2016 [as a % of GDP] is less than (b) public sector net debt as at the end of the previous financial year…

To repeat, this was all set out in primary law – not in or under a Code or Charter but in stark, binding legislation. Moreover, by Section 2, the Treasury could add new legally binding fiscal duties. I find it hard to understand how a government could so box itself in, on matters over which – as we have underlined – it had no overall control.

When George Osborne let it be known, earlier this year, that he too was thinking of new primary legislation to impose budget surpluses, the Financial Times reminded us of the Labour government’s unwisdom, and commented in its editorial (10 June 2015):

As soon as he took office Mr Osborne repealed the law, having previously called it “vacuous and irrelevant”. And rightly so. Had he not done, it would have forced him into further austerity in 2012 and 2013.

So let us be thankful for the small mercy that Mr Osborne has, in the end, resisted the temptation to use primary legislation to impose budget surpluses. He realised that he might end up as victim of his own legislation. Codes and Charters, by contrast, are nice malleable, easily-replaced, politically useful instruments! And that was the path the Coalition government took when it passed the 2011 Act.

Deficits and the golden rule

Now few serious economists consider that modest deficits, especially at a time of very low interest rates, are any matter for concern. More usually, they reflect crisis, weakness (or increased savings) by the private sector. Even George Osborne recognizes that deficits are essential at times of economic recession and crisis, as his new Charter makes clear. In fact, if he remains Chancellor he will have overseen around 9 consecutive years of sizeable deficits by 2019-20!

Currently the percentage of GDP spent on interest payments – despite the post-crash increase in public debt – has remained consistently below the level inherited by Labour in 1997 from the Thatcher/Major Conservative government. It is well under 3% of GDP, another historically low figure for the UK.

It is to note that Osborne’s new draft Charter is softer than Gordon Brown’s golden rule in one respect – it requires a budget surplus in “normal times”, but does not speak of “balancing over the cycle.” It is however far tougher in another key respect – it requires a surplus on the overall budget, whereas the golden rule expressly allows borrowing for investment.

In a recent blog on the Socialist Economic Bulletin (SEB) website , Michael Burke has set out a proposed tactical approach to the Charter that is much narrower than ours in scope; it stays within Osborne’s chosen debt and deficit terrain, while contesting the definition of deficit. He says:

This proposed Act precludes borrowing in normal circumstances/over the course of the cycle not only for current government expenditure but also for investment. It also commits future governments to run budget surpluses, to be overseen by the Office for Budget Responsibility.

As we have seen, there is in fact no “proposed Act”, but a Charter to be adopted under an existing Act. Moreover the draft Charter does not preclude or refer to borrowing “over the course of the cycle”. It instead adopts a binary approach – either we are “in normal times” (then a surplus – of unspecified size – is required for each year), or not (in which case some degree of borrowing is allowed). But these points aside, Burke argues that it is possible to “turn the tables” on Mr Osborne and use the debate and vote to set out clear differences with him, especially on investment policy. He proposes that:

… the aim should be for a balanced current budget over the business cycle, but reserving the right to borrow for state investment. This is the correct position expressed by John McDonnell [2]. This therefore means that an amendment to Osborne’s Bill expressing that position, of no deficit over the cycle for current expenditure but permitting borrowing for investment, should be moved by Labour. This will establish its position clearly.

But, in the likelihood an amendment of this type were to fall, although some other parties may vote for it, then Labour should vote against the entire bill – as it excludes borrowing for investment. (In fact the level of state borrowing for investment currently should be considerable, up approximately 3-5% of GDP). Labour should explain its position of voting against the bill as a whole because of the defeat of its amendment.

The amendment recommended by SEB is identical in form to Gordon Brown’s fiscally conservative “golden rule”. As we have seen, Labour actually almost kept to the “golden rule” over the course of its term until the financial crisis smashed into it. The difference between Brown’s golden rule, and Burke’s proposal, as we understand it, is not in the rule itself, but in the intention that a Corbyn government would have a much larger investment programme than Brown achieved (and will not hide it away under the PFI bushel). The SEB amendment does not mention the “welfare cap” part of the “mandate”, nor whether there should be a separate amendment on this.

Burke’s proposal to draw a legally underpinned line between borrowing for investment but not current budget purposes over the business cycle stands on no firm economic ground. We strongly disagree with the formulation “over the business cycle”. There is no clarity about the length of a cycle, but assuming a given start date, Burke’s proposal implies that the annual surpluses (i.e. taxes raised at levels greater than needed to balance the budget) to be generated in good times may turn out to be enormous in amount and in impact if the prior downturn is severe – as in and after 2008-09. Alternatively, in “normal times” one may have to guess what level of positive balance is needed to prepare for future ‘bad times’!

Now, as we have consistently emphasized, we fully agree with SEB on the need for a large, truly transformational capital investment programme for the future, including modernisation of UK infrastructure. And we agree that this programme should be capable of being funded by government via the sale of bonds, notably while interest rates are at historically low levels. But we share the perspective set out by Jeremy Corbyn (pages 3-4), and which has informed our own proposal:

We all want the deficit closed on the current budget, but there was no need to try to do it within an artificial five years or even the extra five years George Osborne mapped out two weeks ago. If the deficit has been closed by 2020 and the economy is growing, then Labour should not run a current budget deficit – but we should borrow to invest in our future prosperity.

You don’t close the deficit fairly or sustainably through cuts. You close it through growing a balanced and sustainable economy that works for all. And by asking those with income and wealth to spare to contribute more.

If Osborne’s forecasts are right there won’t be a deficit by 2020, but if – like last time – he is proved wrong and he only again manages to halve the deficit then I make this pledge:

Labour will close the current budget deficit through building a strong growing economy that works for all. We will not do it by increasing poverty…

The emphasis here is rightly on the need to give primacy to “growing a balanced and sustainable economy… that works for all”. This, as we have said, should be the principal, and principled, basis of Labour’s policy response to George Osborne’s Charter. In the words of his own critique of Labour’s ill-starred 2010 Act, the Chancellor’s proposals are “vacuous and irrelevant” to the task of rebuilding and rebalancing our economy.

Footnotes (added 11 October):

[1] To be fair to King Canute, he probably knew that his injunction to the sea to recede would not by obeyed, and indeed was trying to make that point. It is less clear that all UK politicians have the same degree of understanding of their limited powers of control over the economy’s waters.

[2] In fact I am not aware of any statement by John McDonnell that refers to balancing the current budget “over the business cycle”