By PRIME economists: Victoria Chick, Douglas Coe, Ann Pettifor

Today, Wednesday 3 August 2011 at 08.00pm BST (GMT +1), BBC Radio 4 will broadcasta debate which took place at the London School of Economics (LSE) on 26 July. This broadcast will be repeated on Saturday, 6 August, at 10.15 p.m BST (GMT +1).

Debaters considered whether Keynes or Hayek had the solution to the present financial crisis. The economist George Selgin and philosopher Jamie Whyte spoke for Hayek; Keynes’s biographer Robert Skidelsky and the economist Duncan Weldon spoke for Keynes.

On the one hand we are pleased that the BBC and the LSE now acknowledge rival positions to the present austerity policies of Western governments. On the other we are concerned that the debate might have served mainly to reinforce existing prejudices, rather than to clarify the substance of the matters under discussion, matters which – there can be no doubt – are of the most profound importance.

Lord Skidelsky provocatively but justly reminded the audience that in the early 1930s, the same orthodoxy driving western austerity policies directed the actions of Germany’s 1931 Bruning government and paved the way for the rise of Nazism. These actions – vigorously opposed by Keynes – were the final straw for a Germany crushed by defeat and the disastrous boom-bust cycle that followed their return to the gold standard. Reparations were easily circumvented by wildly excessive borrowing from financial interests around the world, in a manner that even Keynes did not anticipate. It was these financial and fiscal policies that brought Hitler to power.

With financial interests still firmly in the ascendency and reactionary right-wing forces increasing their grip in the United States and much of the Western world, we must not forget these lessons from history, which formed the background to the original debate between Keynes and Hayek themselves. The stakes are high indeed.

Keynes shared with Hayek a preference for the economy to be primarily the province of the private sector. However, he recognised that ‘the market’ did not always best serve the common good and therefore that state intervention was necessary – and not just during a slump. In this he was diametrically opposed to Hayek.

For Keynes, the market’s major flaws were rooted in monetary arrangements that favoured speculation and excess consumption rather than productive activity. In addition, in a slump, the pessimistic outlook of producers and investors allowed the slump to persist and needed the stimulus of public works expenditure.

The LSE debate neglected the subtleties of the respective positions of Hayek and Keynes and reinforced many of the most common and most dangerous fallacies about Keynes’s contribution – and even established some new ones. While both economists were misrepresented to some extent, our main concern must be to rectify distortions about Keynes. There are eight misrepresentations that we want to bring out.

1. Hayek as “an opponent of financial excess”

From 1971 through the early 1980s, restraints on the financial sector were steadily unwound. These actions were prompted by Hayekian ideals of liberalism, as is well known. The Hayek supporters at the LSE debate dissociated themselves from this liberalisation, the cause as we now know, of the rapid expansion of the money supply before the crash. Hayek might not have predicted this consequence of liberalisation, but its disastrous consequences are now plain to one and all. Perhaps this is why the debaters dissociated themselves from this aspect of Hayek’s position. Instead they castigated the conduct of the liberalisation policy rather than the policy itself. Indeed the ideal of liberalisation was scarcely mentioned, for to do so would be to acknowledge the existence of an alternative: Keynes’s managed financial system.

2. Keynesian policy as “promoting the big state”

Keynes’s most substantial legacy was a financial system managed by the state. This system prevailed from the end of the gold standard until the 1970s. This management ensured that on the one hand low long-term interest rates facilitated both private and public sector investment; on the other, restraints on

banks and capital mobility kept speculation and excessive consumption at bay. Keynes had devised and helped implement a financial system that was conducive to production and investment rather than speculation and consumption. A larger state rightly prevailed than in the 1920s or 1930s, but ironically Keynes’s state was still smaller than the state that prevailed after the counter-revolution of financial liberalisation

The post-war world was one in which the state and the private sector operated powerfully in tandem, supported by a greatly revised monetary architecture.

As we have stressed, Keynes was concerned mainly with the effective operation of the private economy.

3. The inflation of the 1970s as “the fault of Keynesian policies”

The inflation of the 1970s began just after the Keynesian post-war mechanisms for the regulation of finance started to be dismantled. In Britain, controls on banking and capital mobility were relaxed, and liberalised arrangements were restored, beginning with Competition and Credit Control (1971) (evaluated as “all competition, no control” by most economists). The root cause of the inflation of the 1970s was the massive expansion of the money supply that followed the deregulation of credit control, as both Friedman’s monetarism and Keynes’s General Theory, Ch. 21, predict.

The inflation of the 1970s was not the consequence of Keynes’s policies but of the dismantling of his policies for restraining the finance sector. In the past, the inflationary 1970s would have been understood as a ‘bankers’ ramp’.

4. Keynes as “advocate of deficit spending”

While the importance of Keynes’s monetary policies is scarcely recognised, even his fiscal policies are severely misrepresented. Most prominent and pernicious of all is the idea that he advocated deficit spending. From his earliest contributions to the debate on fiscal policy, Keynes was concerned to establish how public works expenditure would pay for itself and would constitute a relief rather than a burden to the public finances. As we have shown in ‘The economic consequences of Mr Osborne’,[i] the outcomes of public expenditure policies over the last century vindicate his analysis. It remains a puzzle why even Keynes’s most ardent champions neglect the evidence.

5. Keynes as “a supporter of wasteful expenditures”

Even after being corrected by Lord Skidelsky in an earlier exchange during the LSE debate, George Selgin repeated the false charge that Keynes supported “indiscriminate spending.”

As Lord Skidelsky emphasised during the debate, Keynes was concerned to revive private investment. He argued that government spending was the only possible means of doing so when businesses were in deep recession (elsewhere Keynes had also recognised the burden of heavy indebtedness on business). Given that the state had to spend to revive the private sector, it was more sensible for government to spend on socially useful activities. But failing that, even spending on socially useless ventures for reviving the private sector was better than nothing.

What Keynes actually said was this:

… ‘wasteful’ loan expenditure may nevertheless enrich the community on balance. Pyramid-building, earthquakes, even wars may serve to increase wealth, if the education of our statesmen on the principles of the classical economics stands in the way of anything better.” [ii]

(Keynes’s attack on the principles that ‘stand in the way of anything better’ continues for a further two pages.)

The sort of misrepresentation that Selgin engaged in serves him and public debate very badly.

Equally fallacious is the Hayekian charge that public expenditure diverts resources from the private activities that should be the basis of any free society. Keynes showed that in a recession no private activity would emerge of its own volition: resources would simply be left idle. To wait for some pre-ordained and virtuous private expansion would be to wait forever while unemployment grew and society crumbled.

6. Roosevelt’s New Deal as “trivial in scale and impact”

The economics profession has recently been willing accessory to the idea that the New Deal was economically without meaning. Sadly – as Selgin trumpeted with some glee during the LSE debate – this idea is associated with Christina Romer, the Chair of the US Council of Economic Advisors in the early years of Obama’s Presidency. Under Romer, the EAC championed fiscal expansion to counter the effects of the ‘great recession’. But Romer appears to have been compromised by her earlier claims that fiscal policy was unimportant in the Great Depression. In 2009 she attempted to set the record straight:

One crucial lesson from the 1930s is that a small fiscal expansion has only small effects. I wrote a paper in 1992 that said that fiscal policy was not the key engine of recovery in the Depression. From this, some have concluded that I do not believe fiscal policy can work today or could have worked in the 1930s. Nothing could be farther from the truth. My argument paralleled E. Cary Brown’s famous conclusion that in the Great Depression, fiscal policy failed to generate recovery ‘not because it does not work, but because it was not tried’.[iii]

But this is to demean Roosevelt’s courage and achievements as well as to misrepresent the facts. Romer’s earlier conclusion follows from a failure to understand that the public sector deficit or surplus does not measure the policy stance, but reflects the outcome of policy. If spending is successful in raising income, higher tax revenues and lower benefit expenditures automatically reduce the deficit.

Instead of relying on abstract analysis in evaluating government expenditure during the great depression, let us look at the figures that are readily available on the Bureau of Economic Analysis website.

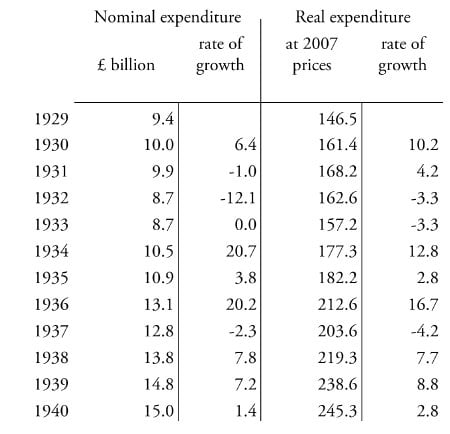

Table 1: US Government consumption and investment expenditures

table

The increases in state spending in the mid-1930s have no precedent in peacetime.[iv]

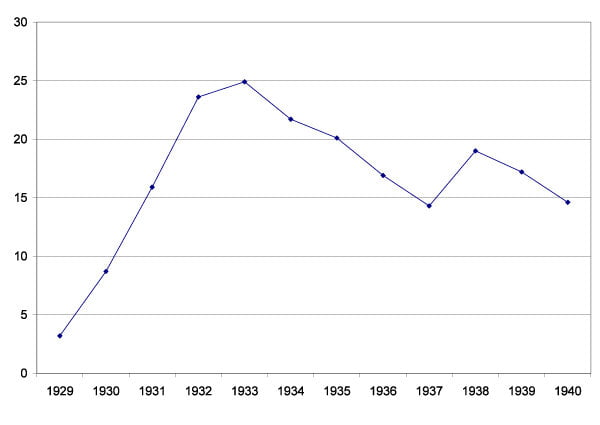

The Hayekians at the LSE debate also argued that World War Two did not bring the Great Depression to an end. The idea is ludicrous from any but the most perverse of perspectives. Note that the end of the Great Depression began as Roosevelt’s spending began in earnest, as this chart of unemployment shows:

US Unemployment rate

US_unemployment2

21 responses

I wouldn’t use austerity and Hoover in the same sentence but equally the idea that the ineffectiveness of Herbert Hoover’s interventions disproves Keynes’ analysis is twisting the truth. Hoover’s small budget deficits could never have stopped the Great Depression. In fiscal year 1930 Hoover ran a federal budget surplus, the first year of the terrible contraction that occurred from 1929–1933. But a root cause of his budget deficits in fiscal years 1931, 1932 & 1933 was the collapse in tax revenues. And his attempt at stimulative discretionary spending increases in the budget in fiscal years 1931 & 1932 were a drop in the ocean compared to the massive collapse in US GDP.

In the 1930s, austerity was tried by President Hoover and by the MacDonald and Chamberlain Governments.

I think that a checking of the fact is necessary. Hoover was a meddler who was a great deal closer to Keynes than to Hayek/Mises. He never tried austerity. “During every year of President Hoover’s administration, from 1929 to 1933, federal expenditure increased.” Hoover’s meddling, like Bush’s and Obama’s prevented the necessary liquidation of malinvestments so no recovery took place for a decade and a half. Contrast this to the 1920 depression in which Harding cut spending and taxes. That depression was deep but short and was followed by a robust recovery. As usual, the Keynesians have twisted the facts to present a version of history that is not supported by the data.

“In the 1930s, austerity was tried by President Hoover”

That’s all I need to read to know you need a history lesson.

1) The suggestion that deregulation was responsible for the sub-prime excess is unfounded. The Glass-Steagall “repeal” of 1999 merely allowed investment banks to have commercial bank subsidiaries; since it was the investment banks themselves rather than their (smallish) commercial bank subsidiaries that got in hot water, the reform made no difference except by making it easier to rescue tottering stand-alone investment banks through bank mergers. As for deregulation in the ’80s, the supposed link to the sub prime boom here is too obviously tenuous to be worthy of comment.

2) It’s true that Keynes himself was what today would be considered a (long-run) fiscal conservative. This is a point I myself made in an excised portion of the debate. However it is also true that the Keynesian suggestion that expansionary policies are generally capable (see below) of combating non-trivial levels of unemployment has been seized upon by politicians as justifying government profligacy.

3) I don’t recall myself blaming “Keynesianism” for the inflation of the 70s. On the contrary: in part of the debate that was edited I specifically observed that Keynes had been a consistent advocate of price-level stabilization. As for the 70s, in the U.S. inflation started creeping up in the 60s, partly because of the Vietnam war but also at the urging of prominent self-styled Keynesians who insisted that higher inflation would bring lower unemployment, as had appeared to be the case earlier in the decade. The so-called stable “Phillips Curve” is not something critics of Keynesianism invented: it was the brainchild of self-styled Keynesians themselves, and it did certainly play its part in the Vietnam-era escalation of U.S. inflation rates.

4) and 5) Whether he intended the consequence or not, Keynes’s “pyramid building” rhetoric licensed wasteful government spending. It’s a shame that he isn’t around to assail those who have abused his arguments so. But even a smallish dose of public-choice theory should have sufficed to predict what politicians would make out of the suggestion that any sort of spending is capable of combating depression and, indeed (if Lord Skidelsky is to be taken at his word) capable of promoting long-run economic growth!

6) Romer wasn’t “compromised” by her earlier writings on the New Deal: she was simply embarrassed by them once she found herself leading the economic team of an administration committed to fiscal stimulus. The evidence and argument contained in her key writings on the 30s remain as solid as ever. Moreover, she is far from alone in having argued that major components of the New Deal, and the NRA especially, were either ineffective or actually counterproductive in ending the depression.

Indeed, Keynes himself believed that the NRA would impede rather than hasten recovery, and said so in a letter to Roosevelt written after the act’s passage. The letter reads in part,

“I am not clear, looking back over the last nine months, that the order of

urgency between measures of Recovery and measures of Reform has been duly

observed, or that the latter has not sometimes been mistaken for the former. In

particular, I cannot detect any material aid to recovery in N.I.R.A., though its

social gains have been large. The driving force which has been put behind the

vast administrative task set by this Act has seemed to represent a wrong choice

in the order of urgencies. The Act is on the Statute Book; a considerable amount

has been done towards implementing it; but it might be better for the present to

allow experience to accumulate before trying to force through all its details. That

is my first reflection–that N.I.R.A., which is essentially Reform and probably

impedes Recovery, has been put across too hastily, in the false guise of being

part of the technique of Recovery.”

(Interested readers can read the whole letter here.)

7) Well, here is Keynesian support for bank bailouts. Q.E.D.

By the way, it has been suggested by some (not here) that in opposing such I in effect favored simply letting banks collapse. But the suggestion that collapse is the only alternative to bailouts ignores what some term the “Swedish approach”, which was the alternative I had in mind.

8) Sorry, but it’s back to pyramids again: the Keynesian argument is that the problem is solely one of inadequate demand, so that, much as public works and such might be preferred, any sort of fiscal should help; and it was on such grounds that U.S. proponents of fiscal stimulus didn’t trouble themselves over just where stimulus money would go in arriving at their (ultimately very wrong) estimates of the “multiplier” effects we could all look forward too. If more orthodox Keynesians think that all this was a mistake, I am glad to hear it. But they still need to explain how to reconcile their ideal stimulus with the workings of real world (democratic) governments.

“A credit-led investment boom diverts capital toward long-term projects. Many of these falter in the ensuing bust. … etc

This is, of course, Hayek’s trade cycle theory, presented most famously in Prices and Production (London, 1931). There is reasons why it is not taken seriously:

(1) Piero Sraffa dealt it a death blow in 1932 in these papers:

Sraffa, P. 1932a. “Dr. Hayek on Money and Capital,” Economic Journal 42: 42–53.

Sraffa, P. 1932b. “A Rejoinder,” Economic Journal 42 (June): 249–251.

The Wicksellian unique “natural rate of interest” required by the theory does not exist in a growing, money-using economy. It does not even exist in a growing barter economy. There is, therefore, no unique natural rate that the bank rate can equal to prevent the alleged cycle effects.

(2) It assumes an economy at full employment and full use of resources, which is frequently an unrealistic assumption in modern capitalist economies. It also ignores the role of international trade.

(3) Even if the full employment and full use of resources condition is met, because of capital reversing and reswitching, the alleged “unsustainable” capital goods investment is not even a necessary outcome at all.

Vienneau, R. L. 2006. “Some Fallacies of Austrian Economics,” September

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=921183

Vienneau, R. L. 2010. “Some Capital-Theoretic Fallacies in Garrison’s Exposition of Austrian Business Cycle Theory,” September 4

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1671886

Again for George Selgin:

I wish I’d had more time to address Lord Skidelsky’s suggestion that one had to be far gone to believe that FDR’s New Deal actually delayed U.S. recovery from the Great Depression. He evidently is unaware of the very substantial body of research pointing to the harm done by certain New Deal programs, and especially by the National Recovery Administration, none of which by the way is due to crazy Hayekians. Indeed, some is by scholars generally considered sympathetic to Keynesian ideas:

http://www.jstor.org/stable/2566501

For Goerge Selgin:

Neither Jamie nor I managed to make as much hay as we ought to have out of Skidelsky’s assertion that government spending of whatever kind is as good as any other sort for promoting long-run economic growth. Here surely was a chance, had we only the time, to draw attention to the rotten heart of Keynesian economics. For Skidelsky’s argument–that workers will supply factories with orders for things no matter who pays them–illustrates in all its naked crudity the dangers of ignoring the “supply side” of economic activity. After all, it isn’t just what workers would like to have in exchange for their paychecks that determines what they can have. On the contrary: what they can have depends crucially on what they themselves actually produce in exchange for the payments they receive. An army of government workers employed digging and refilling ditches, for instance (and the sweeping nature of Skidelsky’s assertion warrants the reductio) contributes absolutely nothing to either its own or others’ ability to consume, let alone to the maintenance or augmentation of the stock of productive capital.

Taken together with Krugman’s ‘How did economists get it so wrong?’ this is an excellent and really helpful primer for anyone who wants to understand what the economic arguments are really about. Thanks.

Nevertheless, I think it is worth underlining the point that Austerians\Hayekians are a truly heterodox and marginal bunch. They are in many ways far removed from the site of the real theoretical and policy battles between Krugman’s freshwater economists and virtually all those who are keen on making the most of Keynes’ insights into the economics of speculation, production and demand.

The Keynes-Hayek debate in the 1930s was an unfortunate distraction, just as it is now. Keynes was attacking “classical economics” while Hayek was responding with Austrian economics. But much of Austrian economics is an attack on classical economics, especially the version that takes root from Eugene Boehm-Bawerk. What was needed was a recognition of the various ways Keynes misrepresented classical economics, including the meaning of such concepts as saving, investment, capital, and money, and most importantly Keynes’s false attribution of “always full employment” assumption to classical analysis. Hayek’s prescription of policy for dealing with the Great Depression never could have been convincing, just as he himself acknowledged, forty years too late!The requirement for producing enough money (cash) to deal with a financial panic in a fractional-reserve banking system was argued by the likes of Henry Thornton, David Ricardo, John Stuart Mill, and Alfred Marshall. Such prescription is also contained in the January 1932 Chicago Memorandum submitted to President Hoover. One can consult J. Ronnie Davies’s 1968 and 1971 books for details.

The failure of Keynes’s modern defenders to appreciate the extent of Keynes’s misrepresentations of classical economics and its policies and continue to prescribe Keynes’s mistaken policies is the real tragedy, in my judgment. To think that the U.S. 2009 stimulus was founded on the mythical Keynesian expenditure multiplier!

Robert Skidelsky is unlikely to have understood the anecdote in his opening remarks in the LSE Hayek/Keynes debate. He related that, in addressing an audience of Cambridge economists, Hayek was asked,‘Is it your view that if I went out tomorrow and bought a new overcoat, that would increase unemployment?’ and that Hayek had replied,

‘Yes, but it would take a very long mathematical argument to explain why’.

Indeed, the argument would take a very long time to explain to economists who lack the basic understanding. Hayek criticised Keynes for not taking time to understand capital theory, and the same criticism applies to Keynesians today.

A credit-led investment boom diverts capital toward long-term projects. Many of these falter in the ensuing bust. ‘Housing’ is the most recent illustration and ‘green’ energy is a likely candidate for the future. As the boom diverts resources to capital projects, fewer goods are produced for more immediate consumption. Yet, expenditures are raised all round. As (in the most recent case) rising property values stoked higher levels of consumption, too little saving again showed as the primary characteristic of a credit-led boom.

As the boom goes bust, there is a temptation to support non-viable projects with state interventions. For an economy to thrive, however, mistakes must be remedied. Where there has been too little saving, it makes no sense to encourage consumers into the High Street to purchase new overcoats.

“It remains a puzzle why even Keynes’s most ardent champions neglect the evidence”

The benchmark used in the paper is nominal fiscal spending, which is… odd. Fiscal spending is set to rise every year under the “Osborne plan” in nominal terms – so you think, on the evidence, it will indeed be expansionary?

“If spending is successful in raising income, higher tax revenues and lower benefit expenditures automatically reduce the deficit”

Tax revenues have been going up this year, in line with relatively strong nominal GDP growth. So again, the evidence implies Osborne plan is working, right?

Read the work of Professor de Soto. Everyone has ignored the effects of fractional reserve banking and the related creation of free money by banks. If you take account of the failures of fractional reserve banking, the Austrian school has actually got it right.

And both sides have yet to recognize the currency itself as a (simple) public monopoly, and all the implications that follow.

Read ‘the 7 deadly innocent frauds of economic policy’ at

http://www.moslereconomics.com

free online

Warren Mosler

Nice article, but I think you are unclear about where exactly Robert Skidelsky distorted Keynes. You say:

“The LSE debate neglected the subtleties of the respective positions of Hayek and Keynes…”

Yes, it was a debate, not a lecture and I thought that Robert Skidelsky, gently but effectively, made the Hayekians look like the complete fools that they are.

Also, your worries about neo-fascist mass movements are very exagerrated. We simply don’t live in a time where politically, things like that are possible. I refer you to Frank Furedi and Spiked-online for more thought on this topic.

A wonderful review of the debate.

I do have one small quesion on stagflation. You say:

“The root cause of the inflation of the 1970s was the massive expansion of the money supply that followed the deregulation of credit control, as both Friedman’s monetarism and Keynes’s General Theory, Ch. 21, predict.”

What do you make of Kaldor’s rather different explantion of stagflation?:

Kaldor, N. “Inflation and Recession in the World Economy,” Economic Journal 86 (December, 1976): 703–714.

More here:

http://socialdemocracy21stcentury.blogspot.com/2011/06/stagflation-in-1970s-post-keynesian.html

There are several things said during the BBC panel session that irritated me. First, if output is driven by spending, even indiscriminate spending does stimulate output. Anything that gets into the circular flow of income will do the job. Like most people though, I’d prefer at least vaguely useful spending projects to ones that involve scandalous waste. But Selgin is wrong to claim that indiscriminately pumping funds into the financial sector can be equated with indiscriminately pumping funds into the circular flow of income through government spending. Keynes did not regard flooding the financial sector with cash as a reliable method to spur spending in the real economy. So the failure of QE to achieve much is nothing that particularly questions the Keynesian approach.There was a lot of stereotyping going on: “Keynesians” favour lots of state intervention (do they?). US bailouts were lots of intervention. Therefore Keynesians can be blamed for the financial system seizing up following these cynical, misconceived and panic-stricken policies. I don’t see why Keynes himself, or Keynesians in general, should get the blame for poorly conceived interventions.

The choice was not solely between “bail them out” and “let the bad banks die”. The problem with the Selgin approach is that the death of the bad banks would kill good banks too; i.e., the entire system (including the good banks) was under threat. Maybe nobody would be left to pick up the pieces. It is hard to believe that a gruesome Fisher-style debt deflation process could occur with the effects confined to bad banks and reckless borrowers. Ideally one would somehow have quarantined and wound up the bad banks – gradually, and ensuring that the shareholders and bonus-takers suffered fully. Instead taxpayers bailed out crooks: there is nothing “Keynesian” about doing this. And of course Selgin is right that it was a crazy intervention to lend to banks at nearly zero and let them use this money to buy bonds paying a rather higher rate and thereby reward them for sitting there and doing nothing. In my understanding Keynesians do not support crazy interventions.

Surely anybody (even Keynesians) should accept that sometimes some aspects of Hayekian analysis may sometimes have some relevance. Greenspan may indeed have left interest rates too low for too long. But we can still be Keynesians and say that it was a good idea in principle to ease liquidity for a suitable time after the bubble, but there was bad implementation in this case that fuelled the next bubble. Hayekians say that easing liquidity must cause another boom and bust, and this goes too far. But on the other hand can’t Keynesians bring themselves to admit that it is possible that poor monetary policy can sometimes fuel a bubble and lead to real over-investment in some sectors?

About Fannie and Freddie: did these companies dominate the scene in Iceland and Ireland? Banks around the world lent too much to people with insufficient means to bid up the prices of houses. Why do so many Americans assume that what may (or may not) be true in the US of necessity applies elsewhere? Banks can foul up even without government help. Even if quasi-governmental instrumentalities aided in building the bubble, there were plenty of private-sector crooks hard at work.

Since when did “Keynesian policies” fail in the 1970s? Narrowly conceived econometric models of the time unsurprisingly couldn’t predict oil shocks or their effects (still less suggest an anti-stagflationary policy response). And the Phillips curve shifted. But these are not failures of Keynes’s model (those in the General Theory and in the Treatise do formally permit supply-side shocks); the fault is with those econometricians and finetuners claiming to be under Keynes’s inspiration. Perhaps Prime Minister Callaghan rightly derided a subset of loopy British leftist Keynesians who may have asserted that the cure for any unemployment is ever more government spending, but the most prominent policy failure of the 70s and 80s surely was the failure of rational-expectations monetarism and attempting to target money.

Those representing Keynes appeared to have a better grasp of Hayek than those representing Hayek had of Keynes.

Only Eight?

And all one the one side?

Listeners’ bias would you say?

Good article to read if you want to ignore Austrian economics instead of asking the question, maybe they are both off, maybe further study and common ground can be found. Typical side taking that divides the nation fueled by confirmation bias or fear that our economic situation may be far worse than Keynesian like to admit.

“makes me think of Whiteheads jibe ” a science wich hesitates to forget its founders is lost” Well OK nether Keynes nor Hayek was Adam Smith but a more wide ranging ( I hesitate to say balanced) critique of the past like this one from Krugman covering more of the anticipated objections might have been a better starting point http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/06/magazine/06Economic-t.html?_r=2&th&emc=th

The propensity of people who argue against Keynes to misunderstand or misrepresent him is astoundingly high. They tend to focus on red herrings such as ‘animal spirits’, which Keynes mentioned but 3 times in TGT, or say he was an advocate for massive discretionary spending and big government, when he simply wasn’t.

Keynes advocated low long term interest rates and banning loans to speculators (as did Smith). With these things, the current crisis simply would not have happened – Austrians claim low interest rates fuel the bubble, but they fail to realise that the worst excesses are always when interest rates are highest (look at CDO issuance and house prices vs interest rates and you’ll see what I mean).

This debate can be interesting/stimulating, but ultimately, it was won convincingly in 1930s – by Keynes, but also by Hayek’s former students, Sraffra & Kaldor. There is no need for us to seriously consider Austrian policy again.

I have not yet finished your piece but as I was proceeding through it I simply had a v. quick question about your third fallacy. I would like to add to the analysis of the 1970s inflation period that, and forgive me if I am mistaken, there was also a large supply-shock, causing cost-push inflation from the oil industry. That will be all. Short of that, all seems well in this piece, thank you for producing it!