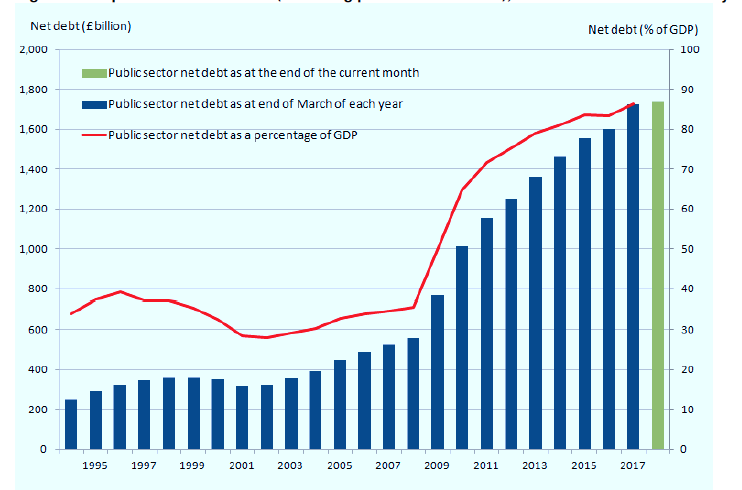

ONS Public Sector Finances, May 2017.

Britain’s public debt has risen inexorably since the Great Financial Crisis. It has done so despite (or because of) austerity, spending cuts that butchered the public sector and local government services, and led amongst other tragedies, to the Grenfell Tower inferno. And because of the very determined efforts of both Labour, Coalition and Conservative governments to cut spending after the GFC – supposedly to reduce public debt – today Britain’s public debt stands at close to 90% of GDP as the chart above from the Office for National Statistics reveals. Under George Osborne’s stewardship (2010-2016) Government debt increased by £555 billion.

We were promised by George Osborne and Nick Clegg in 2010 that cuts to public spending were necessary, nay essential, to restore the public sector finances. We were told that Coalition cuts would reduce public debt to 70% of GDP. Egged on by orthodox economists, shadow Chancellor Ed Balls joined in the consensus, and before the 2015 election promised that Labour would not reverse billions of pounds of spending cuts to the police, hospitals, armed forces and local councils.

Cuts in government spending would lead to a fall in public debt within five years we were told by the Chancellor of Her Majesty’s Treasury. Five years became ten years, and still the public debt rose. Five years have now become fifteen years before we can expect the public finances to be restored to levels that existed before the Great Financial Crisis of 2007-9.

In the meantime not only were public services and welfare benefits slashed, both public and private sector workers suffered an unprecedented deterioration in their working conditions and wages.

While the sheer brutality of the spending cuts may not have been predicted, the rise in public debt was utterly predictable. Indeed Prof. Victoria Chick, Dr. Geoff Tily and yours truly predicted the outcome back in our 2010 publication – The Economic Consequences of Mr. Osborne. But anyone with common sense would have recognised (as the majority of the economics profession failed to do) that by contracting public spending and investment when the economy was (and remains) fragile damages the economy. And damaging the economy, or transforming it into one based on corporate tax-cutting and a low-wage ‘precariat’ invariably leads to reductions in tax revenues.

Falling tax revenues in turn worsen the public finances. Its not rocket science.

That is why Jeremy Corbyn’s team are right to argue that austerity must end. Not just for the sake of the public sector. Not just for the sake of the private sector and the wider economy. But also for the sake of the public finances.

Does this mean a future Labour government cannot borrow and begin to invest & spend?

Okay so total public debt has risen, but does this mean that the British government cannot borrow any more? That increased spending financed by the issuance of government bonds or gilts, will worsen the public finances?

My answer to that is No, No, No. Here is why:

First, while public debt has risen under the dogma of public spending cuts, it does not, I will argue, present a threat to financial stability. It will not deter foreign investors. Indeed there is extraordinarily high demand from investors for Britain’s ‘sovereign debt’. Even after the Brexit vote, demand for UK government gilts was high, as the FT reported here. In trying to understand this, we must understand that a UK government bond or gilt or debt, is a valuable asset. For pension funds, for investors wanting a safe haven for their savings, UK government borrowing, or debt, is an asset they are keen to get their hands on, because they can safely trust that interest on that asset will be paid over the next one or two or three decades. UK government debt/bonds/gilts are valuable largely because they are backed by a sound monetary and tax collection (fiscal) system. That system is sound because the UK has about 31 million taxpayers – that’s me and you, and a new taxpayer born every day. The UK tax collection system – despite tax avoidance and cheating – is efficient and reliable – which means government debt owed to ‘the public’ – i.e. investors – will get repaid. .

But the second point is this: the public (including foreign investors) hold only about 64% of UK debt as a share of GDP. In other words, only 64% of Britain’s debt is exposed to the wider ‘public’ – both domestic and foreign investors.

25% of Britain’s public debt (as a share of GDP) is borrowed from, and held by another government department. It is known as the Bank of England. (Readers will recollect that the Bank of England was nationalised in 1945, largely because of the disastrous part it played in enforcing austerity in the 1920s and 30s.)

In other words, this is debt that the government in effect borrows from itself. Which is why that 89% number is not as scary as many would like us to think. Unlike the UK, the United States recognises the distinction between debt owed by the government to ‘the public’ (i.e. investors domestic and foreign), and government debt owed to the Federal Reserve. If the two are lumped together US government debt amounts to around 106% of GDP. But if the share ‘owed’ to the Fed itself is excluded, total US public debt amounts to only 76% of GDP, as the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis makes clear in this chart. (Note: US government debt at 76% of GDP is higher than UK debt at 64% of GDP).

So, given that Britain’s government debt exposure to public investors is only 64% of GDP, a future Labour government could safely borrow and spend without alarming said investors. Indeed it is highly likely that increased government investment and spending will revive the private sector, raise standards, improve skills and with it productivity and wages – and that those improvements will, in turn generate the tax revenues needed to stabilise the public finances.

And this more than anything else would please foreign investors.

So yes, a Labour government could safely borrow to invest and spend.

3 responses

Ann,

Whatever happened to "Within a sound financial system we can afford what we can do"? (The Production of Money, p6). Apparently confirmed by the paper* among Chancellor Osborne’s 2013 Budget day documents which said: “ …it is theoretically possible for monetary authorities to finance fiscal deficits through the creation of money.36 In theory, this could allow governments to increase spending or reduce taxation without raising corresponding financing from the private sector.”

As it says, increased govt spending without borrowing from the private sector is possible and so could surely fund affordable housing or green infrastructure?

Note 36: For example, A Monetary and Fiscal Framework for Economic Stability, Friedman 1948; and Deflation: Making Sure “It” Doesn’t Happen Here, Bernanke, 2002.

Please let me know that this is not hokum!

Thanks

David Murray

Ann,

I am one of those who support the view that the UK is likely to hit a crisis when interest on the national debt becomes unsustainable.

Although the interest on £1.7 trillion is only 4.5% per household at the moment, a small change in the UK’s AA credit rating could rapidly multiply gilt requirements.

Likely triggers include a fall in GDP after Brexit – or a Labour election victory.

This is the view I was edging towards over the last 9 years, but an organisation called Capital & Conflict is now urging investors to hide their funds before an Argentinian-type collapse.

Possible strategies for Labour are taking a section of the property market as soon as it took office, or requiring investment funds to take a few per cent of the debt.

There would be fury of course. But most of the debt is what private capital passed off in 2008, and the shortfall as Tories sell off public assets at one-third off.

The Labour Party hardly mentions such issues. The floor of conference does not seem a good method. Do you have any suggestions for a how to proceed?

Yours fraternally,

I suggest the above article should have distinguished between borrowing more to fund extra aggregate demand (i.e. extra stimulus) or more borrowing to fund more public spending with aggregate demand held constant. The latter is no big problem. In contrast, the former runs up against the possibility that the economy is near capacity and extra spending will result in excess inflation. Certainly inflation is rising and at the last Bank of England Monetary Policy Committee meeting the “leave interest rates on hold” lot only just outvoted the “raise interest rates lot”.