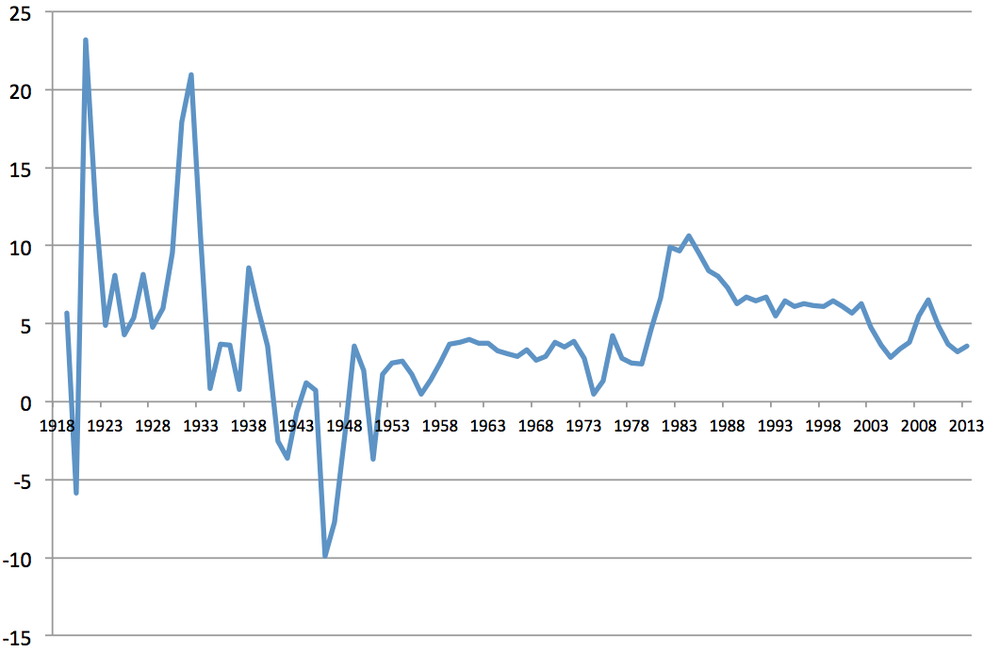

The ‘rate of interest’ has not been low. Instead we’ve had the most prolonged era of dear money on record.

The managed financial arrangements of the post-WWII / Bretton Woods era was decisively ended with the removal of capital controls under Thatcher and Reagan. At this point there was a steep increase in what Keynes called the ‘rate of interest’, “meaning by the ‘rate of interest’ the complex of interest rates for all kinds of borrowing, long and short, safe and risky”

The ‘rate of interest’ has been severely elevated ever since, amounting probably to the most prolonged era of dear money on record.

The real long-term rate of interest

This essay uses recent remarks from Ben Broadbent (the Bank of England’s Deputy Director for Monetary Policy) to motivate a brief review of Keynes’s approach to the ‘rate of interest’.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, monetary factors were central to Keynes’s theoretical and practical approach. Broadbent’s touching on these matters is to be greatly welcomed. He is absolutely right that Keynes would have championed cheap money as essential to any restoration of prosperity. But with his General Theory Keynes turned upside down the conventional theoretical framework on which Ben Broadbent’s position is primarily based. In particular Keynes rejected the notion of natural rates, not least the natural rate of interest.

While the discussion is primarily concerned with the restoration of Keynes’s view, the purpose is not only to try to right historical wrongs. His theoretical analysis leads to practical conclusions of as great a consequence today as it did in the 1930s.

It is wrong to interpret the long-standing reduction in UK gilt-edged interest rates as a reduction in natural rates proceeding on a pre-determined course. They follow instead from a retreat from risk associated with the prolonged and ever-intensifying economic failure of the dear money era. But even in spite of these developments, the current monetary policy arrangement, in spite of exhortations to a future of lower rates, cannot deliver the cheap ‘rate of interest’ that Keynes saw as essential to prosperity. On the one hand, a fuller and more specific commitment to cheap money and actions across the spectrum could be effective given the cooperation of the relevant institutions (Bank, Treasury, Debt Management Office). Moreover the spurious notion of natural rates could be rejected so that they did not stand in the way not only of interest rate policy but also of the kind of expansion in income and expenditure that would permit a fuller recovery including the reduction of debts. But on the other hand, it is unavoidable that the theoretical and practical implications of the General Theory go way beyond incremental changes in policy course.

From the point in December 1930 identified by Broadbent, Keynes went on to arrive at a view of the way a monetary economy operated that turned classical theory and policy doctrine on its head. Over the 1930s, domestic and international monetary reform proceeded at a pace and to an extent that is barely acknowledged. With the imposition of cheap money in the UK and across the sterling area (i.e. the Empire), the effective nationalisation of the Federal Reserve System under FDR, the actual nationalisation of the Banque de France and the 1936 Tripartite Agreement on exchange cooperation between these great nations, for a significant part of the world money had truly been repositioned as intelligent servant rather than stupid master to society (in the later rhetoric of the Labour Party).

More than any other institution (and in contrast with the shameful response of academic economics), the Bank of England has shown itself willing to contest conventional economic doctrine and wisdom.

To read the full version of the publication An Appeal to the Bank of England, click here

One Response

Rejoice BTL Landlords and property speculators.

Who cares about tenants and future FTBs,,