My response to the US Council of Economic Advisers historical perspective on interest rates has just been published in The Real-World Economics Review. [1]

My main objection is to the increasingly common claim that the main trend of note has been a 30-year decline of interest rates. Instead I argue that the most important feature has been a prolonged elevation of rates since financial liberalisation.

Rates were roughly double between 1980 to 2000 compared to the quarter of a century from the end of the Second World War. From a theoretical perspective the CEA deploy the usual conventional explanations that have interest rates as a passive consequence of various behaviours or ‘real factors’ (e.g. savings glut, low productivity). In contrast I argue (following Keynes) that the rate of interest is a policy variable, and rates rose because of the actions of the authorities.

Financial liberalisation was a disastrous failure from the point of view of the alleged aim to reduce interest rates. Real outcomes are a consequence of these higher rates: greatly elevated unemployment, extreme inequality and severe instability have been the norm ever since.

To the extent that rates have been lower recently, this has followed from the exceptional actions of policymakers in the wake of the 2007-08 financial crisis (and ahead of that, the extreme liberalisation in the wake of the corporate crisis at the end of the twentieth century).

I reject the view that interest rates will remain low indefinitely into the future. Such forecasts are based on speculation about the behaviour of ‘real factors’ into the future, and must inevitably be misguided. I warned that there were already signs that corporate borrowing rates were rising, exacerbated by recent dis-inflationary trends.

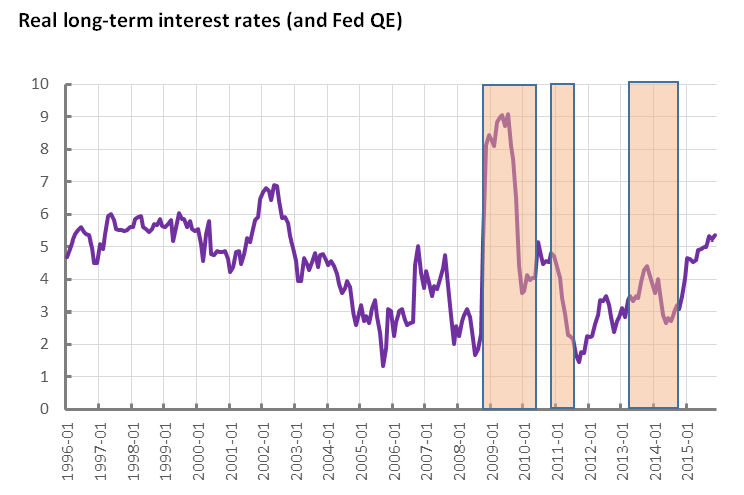

The analysis in my article is based on data from when the work was done in August and September. Since then these observed trends have intensified. The long rate on US BBA corporate debt has now risen by one percentage point over the course of 2015. Taking into account inflation (using the CPI which is constructed on a monthly basis, and projecting unchanged into November), rates over the past three months are now at their highest for eight years and (apart from the extreme increase in the wake of the financial crisis) are returning to territory that was the norm in the last decades of the twentieth century.

While apparently it is highly likely that the Federal Reserve will raise interest rates later this month, the reality is that rates are rising sharply already (see Chart at head of this article).

As Ann Pettifor pointed out earlier this week in the FT, central banks have lost control of interest. The financial system remains dysfunctional, prone to failures of confidence that are the legacy of massive private debts that arose in the first instance from excess borrowing at high not low rates of interest.

This has fostered absolute reliance on quantitative easing. It seems highly unlikely that the real economy is any better placed to tolerate these conditions than at any time since the financial crisis. So any monetary tightening will be short lived.

The answers to this ceaseless inability to move forwards lie in the actions of the US and UK in the 1930s.

Footnote:

[1] First published in two parts on Prime: US Council of Economic Advisers gets dynamics of long-term interest rate wrong and The long-term rate of interest: contrasting the Council of Economic Advisers and Keynes