“I say that if captains of industry cannot organise their concerns so as to give Labour a living wage, then they should resign from their captaincy of industry” – Ernest Bevin, February 1920

One hundred years ago this month, a public inquiry held at the Royal Courts of Justice in London marked a significant change in industrial relations and fostered a wider sympathy for the conditions of working people.

Over two weeks, the ‘Inquiry into Wages Rates and Conditions of Men Engaged in Dock and Waterside Labour’, chaired by the judge Lord Shaw, laid bare the “great human tragedy of men and women fighting year in and year out against the terrible economic conditions with which they have been surrounded”. Beyond pay and conditions, Trade Unions’ call for the dignity of the working class was put “before the conscience of England” (TE, p. 75 – see references at the end).

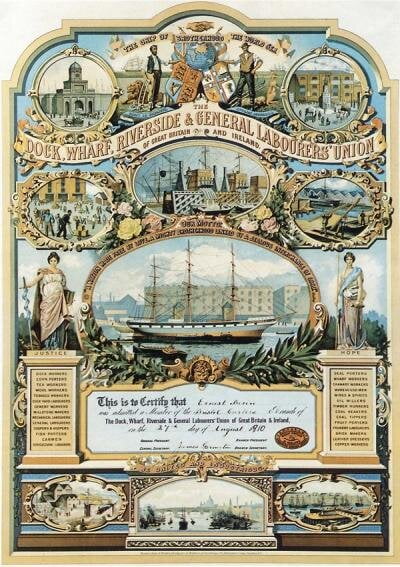

The case for the workers was led by Ernest Bevin, a towering figure in the history of the trade union movement and key member of Clement Attlee’s post-war Labour government. At the time, however, Bevin was national organiser for the Dock, Wharf, Riverside and General Labourers’ Union. Soon coined the “Dockers’ KC” [King’s Counsel] by the press, Bevin (and his team) proved vastly more adept than the employers at gathering and deploying empirical evidence and technical argument – let alone appealing to moral authority – to support his case.

Bevin opened three days of evidence on 3 February 1920; observing it “very novel” for the whole labour movement to submit their claims to the test of public inquiry; they chose to do so:

“… first, because we are convinced of the justice of our claim, and, secondly, because we have no objection to the whole question of the standard of living being open for public inquiry. We hope it will serve not only to obtain what our men desire, but to influence public opinion to a higher conception of what that standard of life ought to be.” [TE, 76]

This article covers the background to the inquiry and the role of trade unions. It is offered not simply as a reminder (100 years on) of a notable piece of history of the labour movement – but moreover one that resonates today, with casualisation, against which the dock workers fought so long and hard, again an all-too familiar feature of work today. It reminds us too of the essential role of collective bargaining to protect labour.

Background

There is a sense, in these events, of something bigger and more deliberate, of renewal after the First World War. At the start of the twentieth century, labour had been growing in industrial and political strength. The Liberal government of Campbell-Bannerman (from 1905) had begun progressive change, and the War itself had meant Labour representation in government and involvement in policy. After the War something better was expected. And there were initially positive signs. New Joint Industrial Councils (Whitley Councils) were established for some industries, so that representatives of employers and trade unions could discuss wages and conditions (effectively establishing the infrastructure for collective bargaining). A 1919 Act established the Industrial Court for the settlement of disputes. It may be that the dockers’ dispute was regarded as a useful test case, and catalyst for change. Trade unions were challenged to show willing to engage in constructive debate rather than conflict; some on the left were mistrustful of both parties to the process.

The dockers – along with the miners – were emblematic of industrial conflict, with the London dock strike of 1889 one of the most celebrated trade union victories. As would be vividly shown, workers laboured hard still for pitiful reward. Above all, dock work was notorious for insecurity, as graphically described by H. A. Mess:

“The foreman stood on the edge of a warehouse and eyed the crowd all over as if it were a herd of cattle. Then very deliberately he beckoned a man with his finger and after a considerable interval a second and a third until he had taken ten in all. There was an evident enjoyment of a sense of power… and the whole proceedings were horribly suggestive of the methods of a slave market.” [cited in AB, 118]

The point of departure to the public inquiry was a Transport Workers’ Federation claim for a minimum wage of 16 shillings a day, a 44-hour week, changed arrangements for overtime and a scheme for the registration of workers.

The chairman of the Inquiry was Lord Shaw of Dunfermline, three elder statemen (Harry Gosling, Ben Tillett and Bob Williams) represented the unions, alongside three of the most influential port employers. After only a couple of days, The Daily Mail marvelled at proceedings:

“We live in truly wonderous times. Imagine a great lawyer like Sir Lynden [Macassey, for the employers] complimenting the forensic skill of a man who until a few years ago was the driver of a horse tramway car, who not only had no education but actually left school at the age of ten. And among the judges constituting the court sits Mr Ben Tillett, M. P., who worked in a brickyard at the age of eight and served as boy in a fishing smack at twelve. The world, after all, does change.

The workers’ case

Bevin reminded the court of the normal business of industrial relations:

“It is true and we say it with pride that, by sheer weight of organisation we have effected improvements, but never yet can I remember a single concession ever handed out to the workmen willingly … The dockers have had one of the highest death rates in this country, due to their irregular life and the horrible slum conditions. Men were injured and it was a common thing for the bullying foreman to say: ‘Throw him in the wing and get on with the work …’ If the men dared to protest…it was ‘To the office and get your money and clear out.’” [AB, 123]

The substance of the unions’ case was to show that a genuine living wage was affordable to profiteering employers. Official claims putting a gloss on recent increases in real wages were contested as misleading. A family budget of £6 a week [around £180 today] was devised as a minimum amount for a “decent life”. The latter included, said Bevin, a “limited amount for luxuries”: “It has been painful for me … to hear employers to whom a guinea stall at the opera is nothing talking about our people going to the pictures”.

Bevin’s case was for the dignity of labour, for a decent standard of living and a good life.

The pay rise demanded was shown as very modest relative to costs, and it was noted that employers always warned of “the ruination of industry”. And yet after every previous increase, “the change brought about such a reorganisation in the industry that the employers were better off”. The nature of the employers’ ‘trust’ (today: cartel) was illustrated, with “practically the whole ramifications of transport controlled by a few people” – “the workpeople were right up against a great form of consolidated capital”.

Ultimately casualisation suited these interests in a far deeper sense than simple convenience for the owners of docks and shipping:

“I am convinced that the employers have always had at the back of their heads that economic poverty producing economic fear was their best weapon for controlling labour. I do not think civilisation built upon that is worth having.” [AB, 125]

And, finally, Bevin made his impassioned call for a living wage:

“I challenge counsel to show that a family can exist in physical efficiency on less than I have indicated. I say that if captains of industry cannot organise their concerns so as to give Labour a living wage, then they should resign from their captaincy of industry. If you refuse our claim, then I suggest you must adopt an alternative. You must go to the Prime Minister, you must go to the Minister of Education and tell him to close down our schools and teach us nothing. We must get back then to the purely fodder basis. For it is no use to give us knowledge if we are not to be given the possibility of using it, to give a sense of the beautiful without allowing us ever to have a chance to obtain the enjoyment of it. Education creates aspirations and a love of the beautiful. Are we to be denied the wherewithal to secure these things? It is a false policy. Better to let us live in the dark if our claims are not to be met.” [TE 78].

The spontaneous applause in the court was so great as he sat down that several minutes passed before it could be silenced. Lord Shaw added his own tribute:

“I desire on behalf of the court to thank you for the care and cogency with which you have presented the case of the workmen. The Court appreciates very much the illuminating way in which it was made.”

Even the Daily Mail was dazzled:

“Mr. Ernest Bevin … has pegged out for himself a place in the front rank of men who count in social politics … He spoke for fully eleven hours, and in the course of his speech presented a formidable array of facts and figures which it must have taken months of study, research and analysis to compile, and which he expounded with a fluent ease and clearness that a Chancellor of the Exchequer might have envied” [TE, 78].

Dismantling the employers’ case

The employers reverted to the (still all-too-familiar) argument that wage increases would undermine British competitiveness. Even at this stage, Bevin had a sense of the macro response (i.e. more wages = more spending = more production = more profit), but in practice focused on the employers’ claims that dockers could live adequately on the wages they were receiving. Sir Lyndon Macassey had submitted a weekly family budget for £3 17s to the court, well below Bevin’s own.

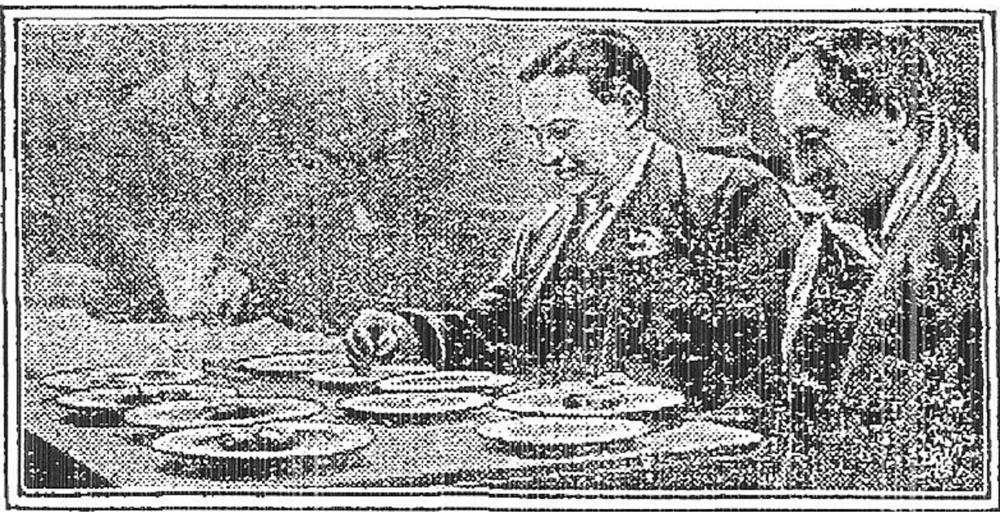

For a while the case took on a theatrical dimension, eagerly lapped up by the press. With his assistant May Fawcey, Bevin went to Canning Town market and purchased food to the amounts allocated in Macassey’s budget. He translated his purchases to a daily budget for a household of five. Under the headline “A cookshop in court: dockers’ K.C. confounds the critics’”, the Daily Express (19 February 1920) reported Bevin’s remarks and the reaction of a witness.

“I have here five plates of cooked potatoes and cabbage, and five portions of cheese. I have not cooked the meat, but I am willing to cook the whole budget to show the court how much counsel allows to sustain a docker for a day.” Mr. L. Brammell, a Birkenhead docker, told the court that he would not sit down to such a meal. ‘There would be a row in our house, I am certain. As to the cheese, if I got to the table first I should have the lot myself,’ added Mr. Brammell amid laughter.

Caption: “NOVEL SCENE AT THE LAW COURTS – At the Docker’s Inquiry yesterday, Mr. E. Bevin, the ‘Dockers’ K.C.,’ exhibited replicas of the meals actually obtained by his clients to-day and what they should receive. The picture shows Mr. Bevin and Mr. Ben Tillett arranging the specimens.”