To understand why neoliberalism is in crisis, it helps to begin at the beginning with Adam Smith. He was the grandfather of market economics, but a more complex thinker than modern day neoliberals like to remember. They hail the ‘invisible hand’ – the idea that self-interest and unmanaged markets work best – and recall his famous discourse on the manufacture of the pin, revealing how the specialisation and division of labour led to huge increases in productivity.

Less well remembered are his observations on the human consequences of that specialisation. The monotony would lead, he wrote, to the worker no longer being able to ‘exert his understanding, or to exercise his invention’ and to becoming ‘as stupid and ignorant as it is possible for a human creature to become.’

Worse, considering how many were to become servants to mass production, whether in a factory or call centre, he thought their ‘torpor of mind’ would take away their capacity for ‘rational conversation… generous, noble or tender sentiment and consequently of forming any just judgement.’

Smith also mocked the very consumerism that his market system would create to feed itself, and was especially sceptical of corporate power, believing that whenever two got together it would lead to a ‘conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.’

Perhaps most surprising of all for latter day neoliberals are his conveniently forgotten views on the vital roles of the state. It should, he argued protect society from violence, protect every member from ‘the injustice or oppression of every other member,’ and critically, ‘erect and maintain those public institutions and those public works,’ which although of great value to society are, by nature, not profitable and therefore should not be expected to be delivered by private enterprise.

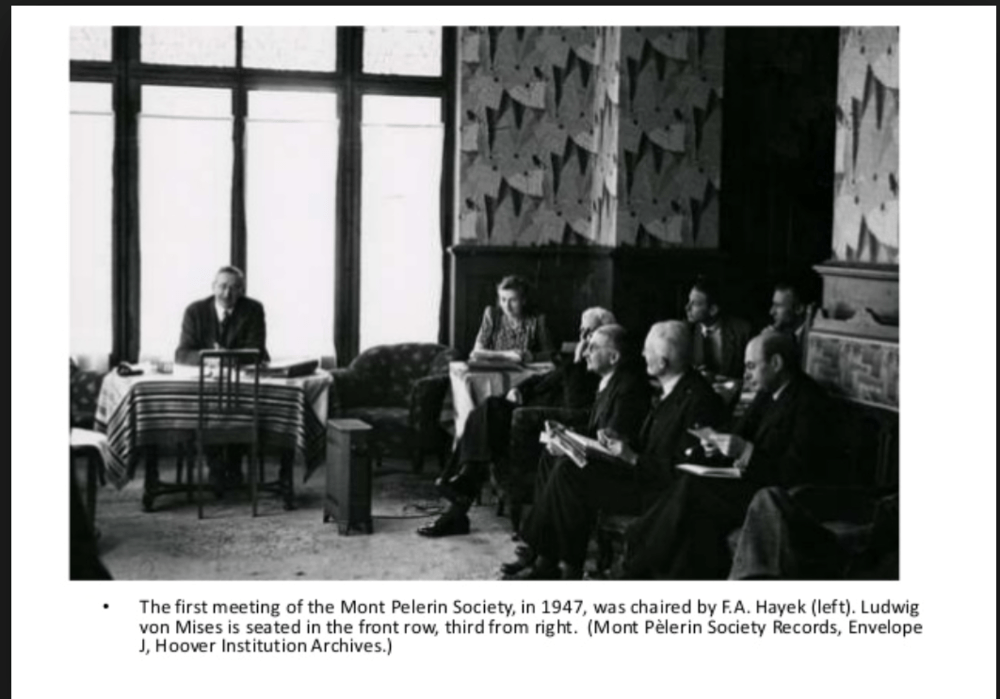

Smith’s forgotten early caveats to his market system are now coming home to roost everywhere from the depredations of the business models of Uber and Sports direct, to failed railway franchises, the painful reprivatisation of banks and the creeping privatisation of the NHS. The demonstrable failings amount to an intellectual collapse of the neoliberal model that began life in the Swiss mountain village of Mt Pelerin in 1947.

A gathering of thinkers and economists ranging from Friedrich Hayek, to Milton Friedman, Karl Popper and Ludwig Von Mises sought to rescue the reputation of market systems from their ignominious failure in the financial crash of 1929, and to champion pure individualism against all forms of collective organisation. The ideological temperature was set by Austrian American, Von Mises, who went so far as to accuse neoliberal scions Hayek, Friedman and others of being ‘a bunch of socialists’. Conservative philosopher, Karl Popper, was there too, one of the founders of the Mt Pelerin Society. But he would later leave complaining that neoliberals were not, in fact, very liberal at all. He saw a fundamental contradiction, that proposing ‘absolute freedom’ would in practice lead to the freedom of the strong to enslave the weak, and deny them their own freedom.

The failure to imagine alternatives to neoliberalism’s coda of self-interest, individualism, private ownership, unmanaged markets and exorbitant privilege given to finance is odd, because successful beacons of different approaches already exist and are emerging everywhere.

In Germany, for example, the financial sector is dominated by banks that are public, mutuals and cooperatives. And the logic of private and shareholder models is being challenged elsewhere in some interesting places. With questions of social media accountability an almost daily news item, a campaign among shareholders and users of Twitter is growing to turn the platform into a cooperative.

It’s not hard to understand the popularity of such moves. The only meaningful way to ‘take back control’ of a world that feels like it’s spinning out of it, is to have some direct say in the decisions that affect your life. And the only way to do that is by being part of them, and that means being part of their ownership and management. Questions of ownership were at the heart of the last UK election. It’s not just about the state, however, but the broader public sphere. This ranges from citizens locally in Latin America deciding directly how their taxes get spent, to the rise of community owned energy. In every such progressive economic experiment steps are being taken towards a great rebalancing, and a new model is being built.

Yet the ghost of neoliberalism still walks, and speaks every time a politician assumes private ownership of infrastructure or a service to be a natural step, rather than their operating in the broader public sphere. In the UK that mindset is revealed when we can’t wait to sell-off public shares in bailed-out private banks like RBS, and flog the Green Investment Bank to ‘vampire’ private bank Maquarie.

Neoliberalism – The Break-Up Tour, by Andrew Simms and Sarah Woods, was commissioned by ArtsAdmin and its debut performance in June 2017 launched the 2 Degrees Festival. It will next be performed on September 14th at the RSA as part of #10YearsAfter

To enquire more about the performance and bookings you can also contact the New Weather Institute