Alongside the empirical account, the CEA find theoretical justification for their 30-year decline (and to aid looking forward) in a host of the usual ‘real’, factors:

- lower long-run growth in output and productivity;

- the global saving glut (in part driven by lower productivity growth);

- shortage of safe assets, like U.S. Treasuries; and

- lower population growth.

(On a shorter horizon they emphasise post-crisis expansionary policy, low inflation and deleveraging of private debt.)

Absolutely fundamental to Keynes’s view was that the long-term rate of interest was in the gift of policymakers. This realisation dawned as he completed the drafting of his Treatise on Money in 1930. “The root causes of what has happened … is to be found in the high level of the market-rate of interest” (CW VI, p 377). As Ben Broadbent (2014), Deputy Governor of the Bank of England, has recognised, Keynes proposed deliberate policy action aimed at “a very great fall in the long-term rate of interest throughout the world”, including “The Bank of England and the Federal Reserve Board … buy[ing] long-dated securities either against an expansion of Central Bank money or against the sale of short-dated securities until the short-term market is saturated” (ibid., p. 386).

Liquidity preference

Only two years later he had devised the theory of liquidity preference. Keynes saw that the long-term rate of interest was not a reward for saving, but the reward for parting with the liquidity of savings (or wealth), after the decision to save (or rather not to consume) had been made. This reward was a psychological factor, to some extent a matter of convention, and convention could be changed.

Over the 1930s and especially in World War Two, he devised increasingly sophisticated debt management and monetary mechanisms that brought the whole spectrum of interest rates under the authorities’ control. The reduction in the UK rate of interest over the 1930s was a result of these deliberate actions and advice. Likewise, Roosevelt too took his cue from Keynes. Fundamentally, policy towards the monetary system was brought under public rather than private authority, under the control of democratic forces rather than ‘vested interests’.

Fiscal policy may also have been essential to recovery, but the new monetary environment was necessary to ensure that it endured:

I am in favour of an admixture of public works, but my feeling is that unless you socialise the country to a degree that is unlikely, you will get to the end of the public works program, if not in one year, in two years, and therefore if you are not prepared to reduce the rate of interest and bring back private enterprise, when you get to the end of the public works program you have shot your bolt, and you are no better off. (Harris Foundation Lectures, 1931)

This statement is a very important and categorical refutation of those who project onto Keynes only fiscal policy and a preference for the state over the market (it is omitted from the published record of Keynes’s work, but was recovered by Richard Kent, 2004).

With the policies successful and recovery ensured, in 1937 he issued his warning that dear money should be avoided like “hell fire” in the face of economic expansion. When war came it was fought with interest rates set at 3 per cent in the UK and 2 ½ per cent in the US (in contrast to World War One, when the ‘hard-faced men’ of the City and Wall Street profiteered from the carnage). His subsequent international initiatives at Bretton Woods and in the UK Treasury were aimed at ensuring the permanent continuance of low rates into the post war era.

The 1945 Labour government

The British Labour government took their cue from Keynes, but they were quickly forced to retreat after his death in April 1946. (“The forces against me, in the City and elsewhere, were very powerful and determined … I felt I could not count on a good chance of victory. I was not well armed. So I retreated”, as Hugh Dalton later put it, 1954, p. 239). Then with the 1951 Federal Reserve Accord, the US Treasury effectively allowed financial interests to reassert their authority over interest rates on government bonds; economists from Chicago had begun to call the shots.[1]

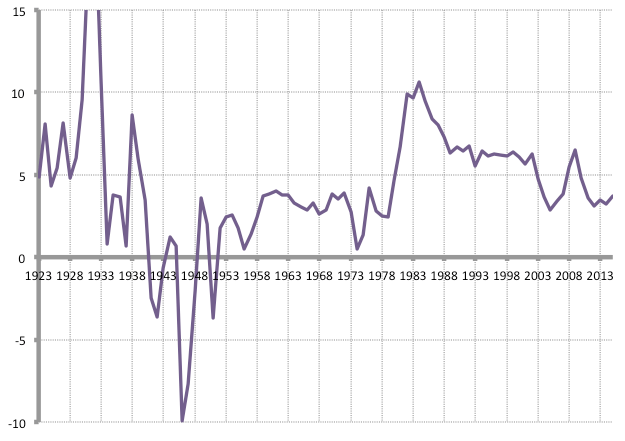

Yet for some 30 years, policymakers permitted relatively low rates to prevail.

But eventually with the Volcker shock and full financial liberalisation, policies holding rates down were decisively abandoned, and, unsurprisingly, rates rose. These rates were the norm for 20 years, and accompanied a severe deterioration in performance, not least crisis after crisis (Germany, Japan, Scandinavia, South-East Asia etc.) that culminated in the global financial collapse and economic recession from 2007-8.

The Council of Economic Advisers may recognise that high rates are detrimental to prosperity, but really their theoretical account has interest as a passive outcome of other macro (really, micro) factors, fundamentally, of course, productivity. For Keynes high rates were the cause of low output, employment and incomes, but they were far more dangerous than ‘just’ that. Animal spirits – more precisely, excessive expectations of income – mean that high interest is not a deterrent to borrowing.

The particular problem of excess borrowing then comes through price rather than quantity, for higher rates of interest are much more difficult to repay than lower. Keynes did not say it, but the outcome is expanding debt, a debt inflation (and for sure in the environment of the great depression of the 1930s he knew it, his commentary on events makes that perfectly plain). On the basis of Keynes’s theory, which emphasised corporate investment expansion and animal spirits, the global financial crisis really began at the end of the millennium. In the light of history, far from a ‘black swan’, it was entirely unsurprising.

Financial crisis

The subsequent reduction in corporate rates followed as a reaction to the crisis, as the authorities allowed the financial system to flood itself with money. (In the UK the vast expansion of the financial sector’s balance sheet was passed over in silence, in spite of the regular, forensic official commentary on the economy.) The financial crisis of 2007-09 came as these actions could be taken no further, and the central bank and governments then took ‘responsibility’ for monetary expansion. With QE apparently regarded as inexplicable theoretically, liquidity preference is perfectly clear cut on the operation of this process. Rates rise as a result of sharply increased liquidity preference in crisis; extending the money supply forces them back down.

The CEA’s judgements about prospects for the rate of interest depend on pure speculation about ‘real’ factors going forward (i.e. resulting from the condition of the economy). On a Keynes view, the trajectory of the long rate depends on policy in the wake of the unresolved crisis of indebtedness. With deflationary forces intensifying and relentless asset inflations, it is unlikely that this process – effectively, repeated demand stimulus through massive liquidity injections – can continue indefinitely.

Devised in the wake of a comparable crisis, Keynes’s theory unsurprisingly offers a coherent and compelling (to me at least) explanation of the behaviour of the economy over the past 30 years as a result of a high long-term rate of interest. The actions of policymakers in the 1930s provide a blueprint for an alternative way forward, to reassert democratic control on the economy and the destiny of the world.

It is tragic – even shocking – that such high authorities can proceed apparently oblivious to Keynes’s interpretation of these matters, let alone to the more obvious events of history. They are victims to a betrayal that has the most immense implications for economics and society.

Opposition to Keynes

The Keynesian economists of the 1930s, including Paul Samuelson, Alvin Hansen, Franco Modigliani, John Hicks and James Meade, are on record opposing Keynes’s approach to the rate of interest. Though in the UK it was left to Dennis Robertson, for many years Keynes’s close colleague, to administer the fatal blow only two and a half years after Keynes had died (undermining too the policy of the democratically-elected Labour government):

Nowadays – I am still talking about high-brow opinion – things seem to have altered in two ways. The rate of interest has come to be regarded as of less importance in the causal nexus, its high reclame [public acclaim] of the nineteen-thirties savouring too much, to the modern taste, of an obsolescent economics of price. (Robertson, 1966 [1948], p. 188-9)

The theory that made it into the textbook and wider literature had no substantive role for the rate of interest. Judged on the basis of this entirely false account, Keynes’s theory and policy has never been assessed on its own merits.

Yet in spite of the crisis and various campaigns for reform of the teaching of economics, such a review still continues to be rejected on the grounds that a theory rooted in mainstream analysis provides a more rigorous justification for fiscal policies to combat recession. That this position prevails beggars belief, though I should concede that even heterodox interpretations only scratch the surface of Keynes’s monetary policies, and my own efforts to convince otherwise, not least in my book Keynes Betrayed, have met with only limited enthusiasm.[2]

As a result, even on the failure of the restoration of the system that Keynes understood as profoundly at odds with stability, prosperity and a just society, financial authority is virtually uncontested in a material way by either academic or political forces. The economics profession needs to wake up to the impossibly high stakes of its ongoing negligence.

References

Broadbent, Ben (2014) ‘Monetary policy, asset prices and distribution’, Speech at the Society of Business Economists Annual Conference, 23 October 2014, available at http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/speeches/2014/speech770.pdf

Dalton, Hugh (1954 [1922]) Principles of Public Finance, London: Routledge.

Hetzel, Robert L. and Ralph F. Leach, ‘After the Accord: Reminiscences on the Birth of the Modern Fed’, Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Quarterly, Volume 87/1 Winter 2001

Kent, Richard J. (2004) ‘Keynes’s Lectures at the New School for Social Research’, History of Political Economy, 36 (1), 195–06.

Keynes (1930), A Treatise on Money; Volume II, The Applied Theory of Money; Collected Writings, Volume VI.

Keynes (1932), ‘Saving and Usury’, Economic Journal, March; Collected Writings, Volume XXIX, p. 13.

Robertson, Dennis (1948) ‘What has Happened to the Rate of Interest?’, Lecture atthe Institut de Science Economique Appliquée’, Paris; reprinted: 1966, Essays in Money and Interest, London: Collins.

Tily, Geoff, (2010) Keynes Betrayed, Macmillan.

[1] An article in the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Quarterly (Hezel and Leach, 2001) contains the reminiscences of Ralph F. Leach, “Chairman of the Executive Committee of J. P. Morgan and Morgan Guaranty Trust. Before joining the Guaranty Trust Company in 1953, he was Chief of the Government Finance Section at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System” (n. 1). “Leach had graduated with an A.B. degree from the University of Chicago in 1938. At that time, Chicago had two of the great economists of the twentieth century, Frank Knight and Jacob Viner. Even at the height of the recession, they and other Chicago economists had retained a belief in free markets. Leach had absorbed that belief and made use of it while at the Board to convince the governors and others of the viability of a free market in government securities” (n. 3).

[2] Mainly on the part of a handful of reviewers (including economist practitioners and Keynes scholars), and notably interest from the Bank for International Settlements: ‘Keynes’s monetary theory of interest’, Bank for International Settlements Papers No 65, Threat of Fiscal Dominance? BIS/OECD workshop on policy interactions between fiscal policy, monetary policy and government debt management after the financial crisis, May 2012. http://www.bis.org/publ/bppdf/bispap65c_rh.pdf