The Polish Presidential election, held on Sunday, resulted in the victory of the (so-called) Law and Justice party candidate, Andrzej Duda, and the defeat of the Civic Platform party incumbent, Bronislaw Komorowski. The Law and Justice Party is generally seen as more nationalist and populist – and pro-American – while the Civic Platform is more pro-EU and economically and socially liberal.

On social issues, the new President is terrible, opposing for example a Council of Europe convention on protection women from violence.

But although socially reactionary, the economic policies proposed by Mr Duda appear to place far more emphasis on social protection, especially of the less well-off, than the Civic Platform. Here is the FT’s not-very-sympathetic summary of his policies:

Mr Duda wants to force local banks to convert Swiss Franc mortgages back into local currency at historical rates, in order to rescue borrowers who found themselves under water when the Swissie soared in January. The government has already laughed off such a suggestion, to the relief of lenders. But Mr Duda wants to push ahead regardless, despite projections that it would cost banks more than $10bn and push many into bankruptcy.

Pensions: Another central plank of the campaign manifesto was the president-elect’s plan to reverse a politically unpopular increase in Poland’s retirement age to 67. The pledge was a sop to older voters, who traditionally back his right-wing party. It would cost Poland’ pension pots an estimated $19bn over the next five years.

Tax: Mr Duda wants to jack up the tax-free slab for Poland’s lowest-paid workers from $800 per year to $2,100 per year. He says it will help millions who did not see their salaries rise during Poland’s recent economic expansion. But the country’s finance ministry says the measure will cost other taxpayers as much as $5bn a year.

His business agenda emphasizes protection of national industries:

“Polish entrepreneurship should be protected and supported, for example by putting the tax burden on large [mainly foreign-owned] networks of supermarkets, which in relation to their revenue pay peanuts in taxes. One needs a tax here,” he said.

And also bank renationalisation; again from the FT:

Two-thirds of Poland’s banking sector is controlled by foreign lenders, such as Italy’s UniCredit, Spain’s Santander and Germany’s Commerzbank. Mr Duda has suggested a gradual renationalisation of the industry, amid scorn from independent business analysts. If Law and Justice were to win parliamentary elections in October, they would take control of Poland’s financial supervision and its largest state-owned enterprises, which could have the clout to start buying up banking assets.

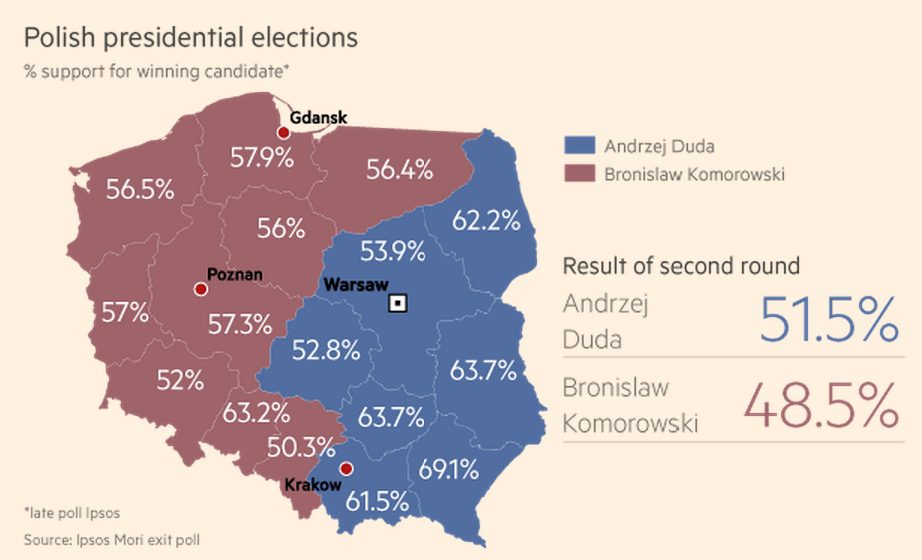

The most striking fact about the election result is the east-west split, almost reminiscent in this sense of the Ukraine’s, though arising for very different reasons. The following map (also from the FT, and using exit poll figures) shows this division absolutely clearly:

There appear to be two strands behind this regional division – a geopolitical aspect, and an economic aspect. It is surely no coincidence that the regions closest to Russia voted for a more hard-line party on defence and NATO.

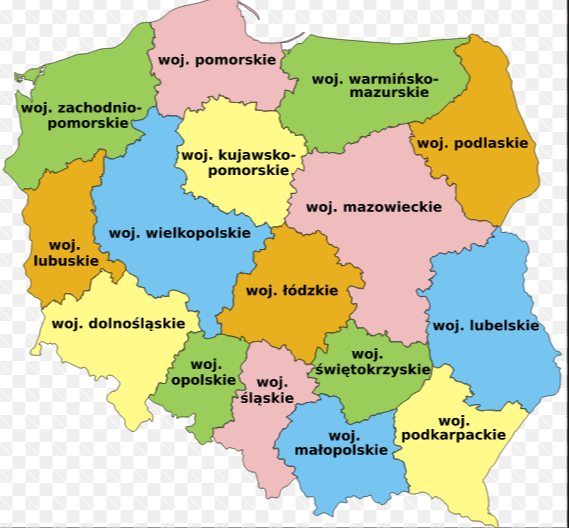

But there does also seem to be an economic dimension, since on average the regions that voted by majorities for Mr Duda are poorer (in GDP per head) than the regions voting for Mr Komorowski and the Civic Platform. Since the above map does not name the regions, here is another map which makes good this defect:

Here now is a list of the Polish regions, starting with the least percentage of votes for the winner, and ending with the region with the highest, showing their GDP per head (latest figures I have found from Eurostat are 2011) and whether they voted D for Duda, or K for Komorowski:

The correlation is certainly not perfect – and is affected by the fact that the Mazowieckie region includes the capital, Warsaw. But the four poorest regions all voted by the largest margins for Mr Duda.

So we see again that the poorer sections of the community, in many different European countries, are voting for parties that appear to offer more protection from the chill winds of economic liberalisation. The Law and Justice party offers some economic and business policies that resemble those of the Front National in France.