The Fallacy

I recently had a conversation with a former civil servant who is a member of my Labour constituency organization about the shadow chancellor’s promise to increase public investment. He agreed with the need to do so, but challenged me with the question, where will Labour find the money to do this?

The quick answer is, by borrowing. A country with its own currency never runs out of money, because its government can borrow in financial markets or from its central bank. The Bank of England, part of the public sector, holds almost 30% of the UK public debt.

However, underlying this simplistic phrasing, how to “find the money”, lies a more fundamental issue. Investment is by definition expenditure for the future not the present. Therefore, while it appears as spending in the future, in the present it can be viewed as non-spending, by definition “saving”.

Since investment represents saving in the current period, is it necessary for private sector business and/or governments to save in order to invest? Recently at an anti-austerity meeting a speaker maintained that the answer is “yes”. The argument went as follows.

Image the simple case of an economy with one product, maize. In order to produce maize in the next growing season, farmers collectively must set aside part of this season’s maize as seed for next season. To keep production at the same amount each season the same amount of seed must be set aside. To increase production next season, farmers collectively must set aside an increased amount of seed for planting.

Thus, it seems that increasing production initially requires that less maize is available to eat during the current period. The reverse holds – increasing consumption this season means less production and less consumption next season. To increase consumption increases in the future, consumption must decline in the present.

This apparent dilemma – more in the future requires less now – is a well-known parable in mainstream economics. In a commonly used economics text book we read,

For society to invest more in capital, it must consume less and save more of its current income…[Growth] requires that society sacrifice consumption of goods and services in the present to enjoy higher consumption in the future. [page 141]

When applied to the public sector, this generalization would imply that if governments borrow they should do so to invest, not to consume. To use the common UK budgetary terminology, our government should cover current expenditure with current revenue. Borrowing to invest draws saving from the private sector to fund public capital projects. It is the strict equivalent of setting aside more seed for the next growing season.

Applying the farming parable to government implies that deficits on the current budget undermine economic growth, because the borrowing by the government transforms private sector saving into public sector consumption (private investment into public consumption). Borrowing for current spending impoverishes; borrowing to invest enriches.

Where the Fallacy Lies

As reasonable as it may appear, for a market (capitalist) economy this analysis is false. The conditions for it to be correct do not exist in the real world. The most obvious requirement for the parable to hold true is that the hypothetical economy operate at full potential (“full employment”).

If all of society’s resources are in use, producing more of one thing requires producing less of others – more investment goods require less consumption goods. The UK economy is not now and rarely in the past has it been at full capacity (and the same applies to most countries, Weeks chapter 4).

As should be obvious – even to writers of economics textbooks – if resources are idle more consumption goods and more investment goods can be produced simultaneously. When resources are idle, investment generates saving not vice-versa, one of the principal insights of J M Keynes (perhaps first appearing in a pamphlet written with Hubert Henderson).

Before Keynes, Karl Marx made a very similar argument, ridiculing those who believed that capital accumulation required prior saving by capitalists. Marx explained that accumulation results from capitalists borrowing to hire idle labour (found in Capital Vol I, “The General Law of Capitalist Production”).

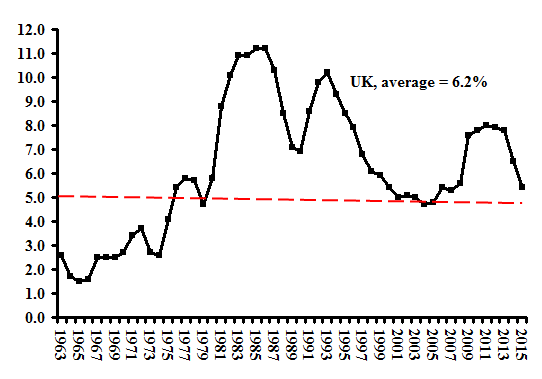

Despite the Chancellor’s claims that the UK recovery is robust, our economy displays all the signs of performing well below potential. The present unemployment rate of about 5.5% seems good only by comparison to the disastrous years since 2008. By contrast, over the years 1963-1979, the unemployment rose above 5% in only three (1976-78).

After 1979 unemployment barely managed to squeeze under 5% in only two years (2004 and 2005, both at 4.8%). As Ken Livingstone said in his speech to the Labour Against Austerity meeting, in the 1950s and 1960s “full employment” meant unemployment less than 2%. Data on capacity utilization further undermines the Chancellor’s recovery bravado, since it has fallen for the last three quarters (Figure 2).

Figure 1: UK Employment Rate, 1963-2015 (% of working age population)

Source: OECD “standardized” unemployment rate

Figure 2: UK Private Sector Capacity Utilization, 2013Q1-2015Q3

Source: Trading Economics.

2 responses

"A better measure of spare capacity is inflation."

How is inflation a better measure of DOMESTIC ‘spare capacity’ than measures of actual utilization of domestic real resources, including labor power?

The fact that unemployment is currently around 5% as compared to about 2% in the 1950s and 60s doesn’t prove there’s a lot of spare capacity. Reason is that the labour market of the 50s/60s was quite possibly a different kettle of fish to the 2015 labour market.

In the 50s & 60s most adults had memories of the 1930s plus they’d just been thru WWII. They were grateful for a job. Come the 70s and 80s I suggest they, and their union leaders, became a lot more stroppy.

A better measure of spare capacity is inflation. At around zero percent clearly that’s on the low side right now, so I agree there is SOME spare capacity. On the other hand, as I understand it, once the recent collapse of commodity prices has washed thru the system, inflation will rise by about 1%, all else equal.