This article was first published on the Prospect magazine website on 15th October 2017

“Strong and stable” seems of a world so far, far away. The recent Daily Mail headline “PM slaps treacherous Chancellor down” portrays a government in political chaos. Thanks to open, unresolved intra-Brexiteer warfare, ministers are unable to agree the basics of how to exit the European Union. This state of uncertainty intensifies just as the risks to British jobs and living standards are becoming starker and more potent. Ironically, just as we teeter towards the cliff, ONS data reveals that exports of goods to the EU grew over the last three months, while those to the rest of world fell back, a fact not devoid of dark humour.

Yet while ministers appear obsessed by trade, net trade comprises only a small part of UK GDP. Surely, through the coming period of Brexit chaos, government priority must be to “take back control” and maintain and support the domestic economy. This means a commitment to support not only investment technically defined as “capital” but also public investment in the health, education, and training of the British people. In that way, Britain will have some chance of weathering the storm.

George Magnus highlighted the OBR’s acceptance that UK productivity growth is likely to stay much lower than previously assumed. This leads to the inevitable conclusion that—on present course—the ever-weaker economy will lead this government to continue to slash public revenues. Yet even this gloomy OBR data underestimates the dangers. For the OBR has not yet factored in the far greater damage that will flow from a chaotic, unplanned Brexit in less than 18 months.

At the core of government dissension is an unresolved dilemma—which ideological path to pursue? On the one hand, the fanatics within the Conservative Brexit camp support ultra-free markets and echo the deregulatory ideology of the US Republican Party. They press for a hard Brexit because for them, the future subjection of the UK—and of course our public services—to the economic interests of US capital is assumed to be beneficial, and therefore paramount. Hence the calls for the UK to join NAFTA.

Yet at the same time, as polling by Lord Ashcroft and Legatum has shown, UK citizens are decidedly downbeat about the way markets work in the UK. They seek order, security and protection from the impact of self-adjusting market forces. Hence the government’s hasty action on energy prices.

UK’s low investment, low productivity record

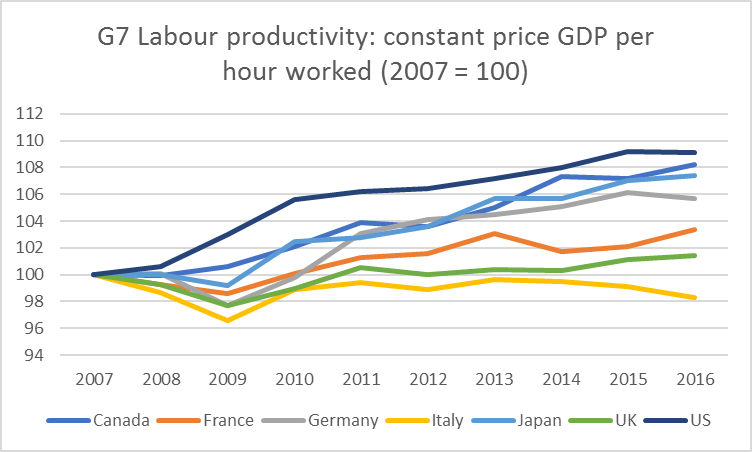

But underneath the short-term dangers lie the longer-term problems for the UK economy. The “puzzling” decline in productivity is strongly correlated with Britain’s low levels of public and private investment in the domestic economy. While the UK regularly has the highest levels of Foreign Direct Investment in Europe, overall UK investment has long been the lowest in the G7 (recently Italy’s fading economy has slipped even lower). While other developed economies have also seen a relative productivity slowdown since the financial crisis hit in 2007, the UK has the second worst record, next to Italy.

Investment in the UK has since 2007 been in the 14 – 18 per cent range as a share of GDP. In 2016, the figure was 17 per cent. France, by contrast, has annual investment of between 22 – 24 per cent of GDP, and Germany around 19 – 21 per cent. The UK in 2016 slumped to 116th place out of 141 countries in terms of capital investment as a percentage of GDP. In the EU, only Greece, Portugal, Lithuania and Cyprus were below us.

Low levels of investment by the “timid mouse” that is the private sector (to use Mariana Mazzucato’s characterisation) is directly a function of low levels of aggregate demand. Firms can’t see future customers coming through the door, and are made timid by volatile financial conditions and political uncertainty. Weak demand and financial instability are exacerbated by low levels of public investment.

At PRIME, we have long pointed out the many similarities between the UK and French economies. Both countries produce roughly the same GDP. The difference is the French economy has high productivity allied to high unemployment. The problem confronting both countries is the weakness of aggregate demand, made worse by Eurozone and UK austerity policies.

Will Hammond tighten the austerity screw?

UK unemployment has fallen to levels not seen for generations, and employment continues to climb above forecasts. But it is evident to all who will look that this increase in employment is mainly in “less productive” industries. In Britain, labour has been substituted for capital.

Which brings us back to Philip Hammond who proposes a further tightening of the austerity screw on public services next financial year. The “negative multiplier” (the contractionary effect of reductions in government expenditure) which already serves—as the IMF has shown—to reduce the likely level of GDP, will be made worse when Brexit chaos is factored in. This tightening was always utterly perverse, since in 2016/17 the current budget deficit (before investment) was under half of one percent of GDP. No sensible economist regards that as an issue to worry about. Indeed, the Conservative government of the early 1990s maintained current budget deficits that averaged over 3 per cent per year for six years.

Phillip Hammond argued in the Times on 11th October that the government is “planning for every outcome and we will find any necessary funding and will only spend it when it’s responsible to do so.” A government endowed with a central bank is never “short of money.”

But what is it for a government to be “responsible”? That is a political, not economic, judgment. We face (a) a slowdown in projected future GDP in any event, before and after Brexit, and (b) an ever-more possible chaotic under-planned Brexit in March 2019.

If the government were now to double down on its post-2010 austerity dogma, with ever-deeper cuts in public service spending in the deluded quest for deficit reduction, it would be adding further contractionary forces into an already slowing or contracting economy.

That would be economic madness.