Originally published by EREP on 23th February, 2015

This is a briefing from Economists for Rational Economic Policies. These address major current issues affecting the UK economy, in particular those associated with counterproductive “austerity” policies. To read as a pdf document, download here

As we approach the General Election of 2015, there is a strong risk that any discussion of economic policies will be mired in a false and sterile debate around “eliminating the deficit”. This is the first of two linked briefings on the theme of austerity, deficits and debt.

A combination of government ministers, right-wing think-tanks and the media have for the last few years combined to persuade the British public that elimination of “the deficit” via austerity policies should be the single essential goal of economic policy – and that it is foolish and almost unpatriotic to deny this!

We disagree. Since at least the 1930s, both theory and practice have shown that deficits often play an essential and positive economic role, and that a fixation on eliminating deficits by contractionary fiscal measures is counter-productive. History shows that it is mainly by increasing investment and productive (and decently remunerated) work that we achieve more balanced budgets.

There are some excellent recent analyses of why the current political “fetish” for austerity and deficit-elimination (to the exclusion of other goals) is not only misconceived but is based on untruths.

Here are two easy-to-digest examples we recommend from prominent academic economists:

Professor Simon Wren-Lewis: “The Austerity Con”, London Review of Books, 19th February 2015

Professor John Weeks: “Pain, No Gain: the Austerity Scam”, PRIME economics, December 2014

Remembering how we got here!

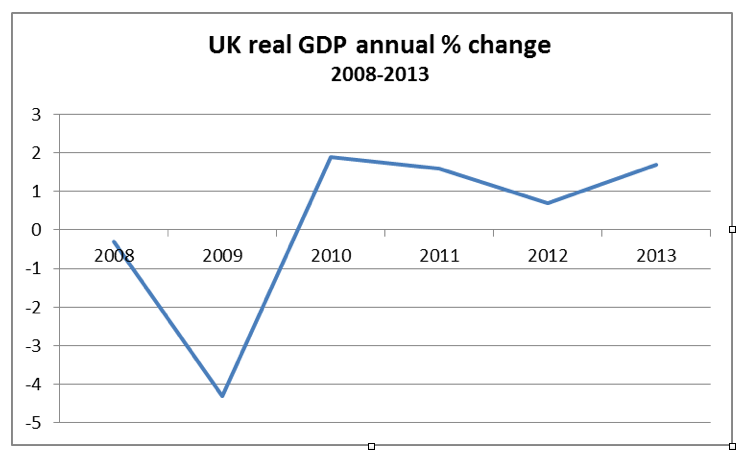

When the financial crisis caused the global economy to implode over 2007-9, it was British and American taxpayers, via the public sector, that first took the strain. As the private sector contracted, as output collapsed and unemployment rose, both the UK and the US governments replaced the gaping hole left by the private sector with a cautious (and relatively modest) expansion of public sector spending. The Eurozone and other countries quickly followed down a similar path.

The 2008-09 crisis was not a UK phenomenon caused by the Labour government, but a crisis of the globally interconnected private financial system. It hit all developed economies, whether their government was of right or left. The Labour government made policy mistakes of under-regulation and excessive growth of the finance sector – but these were shared policy errors with the Conservative Party in the UK, and with international partners of different political hues.

If our governments had not reacted as they did, the crisis would have inflicted a double whammy: the failure and contraction of both private and public sectors. Instead, the public sector stepped in to support people affected and to bail out the private sector. A vast £350 billion was pumped into the City of London by a nationalized bank – the Bank of England. Taxpayer subsidies were provided to e.g. the motor industry (“cash for clunkers”), and more recently, by the Coalition government, to the banking system via the 2012 Funding for Lending scheme; and for banks and the private construction sector via “Help to Buy”.

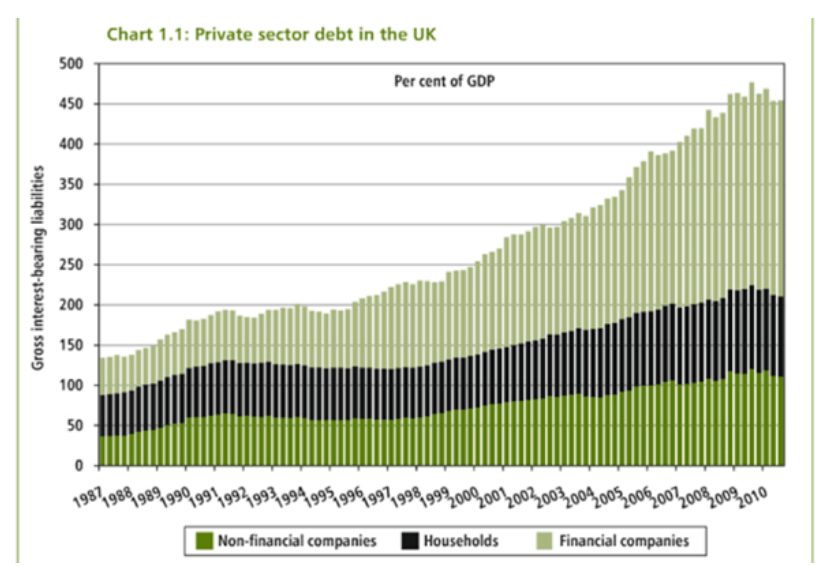

In 2010, even Chancellor George Osborne had recognised that the global crisis was mainly a crisis of private sector debt – including the UK but also most other “developed” economies. In the 2010 June Budget, we find this chart showing the growth – under both Conservative and Labour governments – of private debt in the UK by sector since 1987 (note the rise in financial sector debt):

2 responses

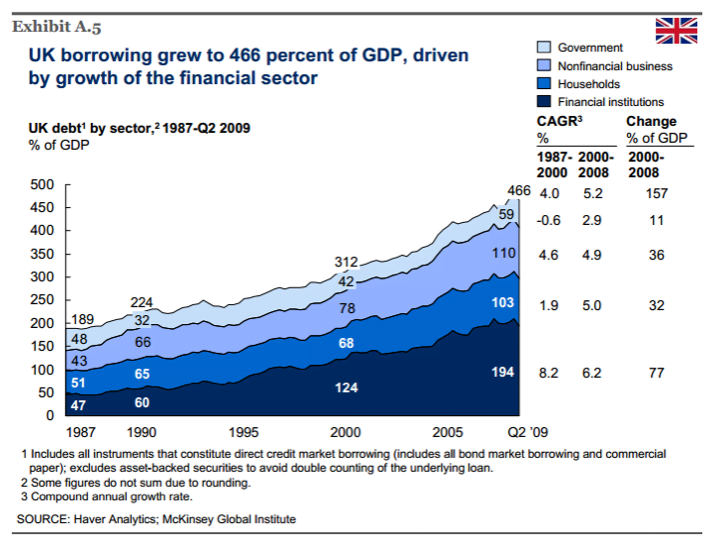

Thanks Stephen for comment. The purpose of the McKinsey chart was not to equate public and private debt, but simply to illustrate how small public/government debt (or ‘debt’) was at the onset of the financial crisis compared to private debt. We are trying in these briefings to engage with politicians and media who have been bamboozled into believing that the crisis was one caused by public debt, and whose starting point is a million miles from MMT’s.

"For the greatest misconception…is that running a government’s finances involves the same issues and principles as running one’s own private household. This is false."

Then why undermine that perfectly correct statement of fact by presenting a McKinsey Global Institute chart that, misleadingly, compares government ‘debt’ (which is entirely un-burdensome) to ‘households’ (aka the private sector) that really do feel the burden debt? Such a comparison is meaningless and serves only to confuse the reader.

That and talk of taxpayers ‘taking the strain’ leads me to conclude that the author (and perhaps PRIME as a whole?) have a rather less comprehensive and cohesive understanding of government finances than do leading MMT economists such as Randy Wray and Bill Mitchell.

Sadly MMT is mainly US/Aussie based, so come on PRIME please get your act together and invite these guys over to the UK!

PS The only Brit MMT academic I have come across is Aussie-based Steven Hail…

https://vimeo.com/117137212