Exchange Rates, External Constraints, and Social Stability

By Matías Vernengo and T. Sabri Öncü

This article first appeared in the Indian journal, Economic and Political Weekly, on 17 January 2026. Matías Vernengo ([email protected]) is with Bucknell University, Lewisburg, Pennsylvania. T Sabri Öncü ([email protected]) is an independent economist based in Istanbul.

Argentina’s current economic strategy, increasingly premised on exchange rate adjustment as a panacea for external imbalance, rests on theoretical misconceptions and empirical misreads of how exchange rates interact with commodity dependence, global demand, and capital flows.

Under the shadow of an evolving geopolitical context, a new Monroe Doctrine has taken shape—or the Donroe Doctrine, as it was aptly called by the New York Post—epitomised by direct military action against Venezuela and the forcible removal of its president. In this context, Argentina’s dependence on external financial and political support further complicates the prospects for autonomous economic policy, as geo¬political enforcement increasingly operates alongside financial conditionality to delimit the boundaries of permissible policy choices. The policy framework being advanced by the United States (US) administration—and by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which remains effectively dependent on the US—has been instrumental in propping up the Javier Milei administration, yet is far more likely to undermine the prospects for stability and recovery than to promote them. [1]

There is a growing consensus, shared by both progressive and conventional economists, that Argentina’s exchange rate is overvalued and must depreciate. Following its most recent bailout of Argentina in April 2025, the IMF has also strongly advocated a more flexible exchange rate regime and a depreciation of the peso. The agreement reached with the government established a band within which the peso is allowed to fluctuate, with the band initially crawling at approximately 1% per month. This crawl was recently adjusted so that the band’s movement now tracks the previous month’s inflation rate, implying an effective depreciation of roughly 2.5%, at least for now.

Implicit in this view is the idea that there exists some equilibrium price of the domestic currency, or equivalently, a price of the US dollar in pesos, that would inherently solve Argentina’s external problems.

Argentina’s external difficulties stem from its inability to earn sufficient foreign currency to obtain the imports necessary to sustain economic growth and to service its foreign debt. To generate foreign currency, a country must export. The conventional argument is that a more depreciated exchange rate would make Argentine goods cheaper on international markets, thereby boosting exports enough to remedy its balance-of-payments problems.

While many analysts, including ourselves, disagree with this prescription, it is important to understand the logic behind it. The notion that there exists an equilibrium exchange rate capable of resolving Argentina’s external constraints is flawed. There is no such natural exchange rate that ensures the country can both pay for its imports and service its foreign obligations, just as there is no single natural interest rate that guarantees stable prices and full employment. The foreign exchange rate, like the interest rate, is a conventional price, as John Maynard Keynes noted long ago. [2] A depreciation, therefore, does not inherently lead to an optimal equilibrium. If Argentina were to allow the exchange rate to float freely, without any management, there is no guarantee that it would settle at a stable value, let alone one that would resolve its external constraint problem.

Indeed, under current conditions, the peso could depreciate indefinitely, with profoundly negative consequences for the domestic economy. Milei’s administration, propped up by Donald Trump, has so far managed to avoid a collapse. The dilemma is whether to accept the conventional view that there exists a correct price for the exchange rate, allow the exchange rate to depreciate, and risk a return to high inflation, or instead attempt to stabilise the nominal exchange rate, which implies foregoing reserve accumulation, at least in the short run, and anger the IMF and the US administration. Given the current subservience of the Argentine government and the belligerent external posture of the US in the region, the prospects are grim.

How We Got Here

To understand the present situation, we must trace Argentina’s crisis back well before the current administration. The economic instability that plagues Argentina today began in earnest in 2018, under the government of Mauricio Macri. [3] During this period, key figures who are now part of the current administration, such as former finance minister Luis Caputo and former central bank governor Federico Sturzenegger, negotiated a major IMF programme. Macri’s decision to repay holdout “vulture funds” (Öncü 2014a, 2014b; Vilches and Öncü 2015) in full allowed Argentina to re-enter international financial markets after more than a decade of relative exclusion. Initially, capital inflows bolstered central bank reserves, but, by late 2018, capital flight eroded those reserves, while foreign debt, which had previously been more or less under control, more than doubled. [4]

Exports failed to grow sufficiently as reserves dwindled, leaving Argentina unable to meet its foreign obligations through either export earnings or reserve accumulation. This situation is almost unique among middle-income countries in the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2008–09. Most countries responded by accumulating reserves, typically by maintaining a positive interest-rate differential, that is, the difference between the domestic interest rate and the foreign reference rate, adjusted for country risk and expected depreciation. Argentina, by contrast, under both populist and neo-liberal administrations, maintained relatively low interest rates, making it consistently more attractive to hold dollars than pesos. This, in turn, effectively led to the informal dollarisation of the Argentine economy (Amico et al 2022).

The depreciation of the peso, in turn, also implied that the price of imported goods rose, putting upward pressure on the general price level. Wage renegotiations forced readjustments to maintain purchasing power, and the resulting exchange rate–wage spiral—the distributive conflict characteristic of an open economy—kept inflation high. In fact, under Macri, inflation accelerated, growth stagnated, and in 2019, he lost the re-election bid. The subsequent administration of Alberto Fernández (2019–23) saw inflation continue to rise, exacerbated by the economic effects of the pandemic, which pushed up the cost of many imported goods.

The election of Milei in late 2023 came in the context of rampant inflation and chronic stagnation, going back to 2011, when the current account surpluses associated with the commodity boom had run their course.

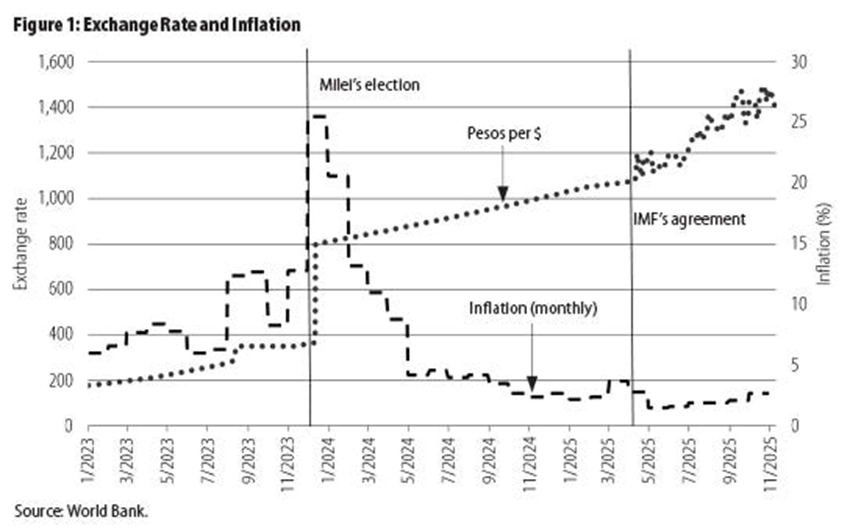

One of his first actions was a large depreciation of the peso—nearly 100% in December 2023—intended to reduce real wages. The resulting strong pass¬through to prices sharply eroded purchasing power. In the following months, the Milei administration adopted a managed exchange rate regime, capping depreciation at roughly 1% per month while maintaining the capital controls originally introduced under Cristina Fernández de Kirchner in 2011 and re-established under Macri in 2018. By stabilising the exchange rate and limiting imported inflation, Milei eventually brought inflation down from its peak. However, he lost the September 2025 provincial elections in Buenos Aires, largely due to voter dis¬satisfaction with economic conditions and austerity measures.

Following this setback, Milei secured US backing ahead of the October 2025 national legislative midterms, which he won despite low voter turnout. Notably, as seen in Figure 1, he had accelerated inflation before bringing it back down.

Many argued that the more recent run on the peso started because of the electoral defeat in September. But it was only after the IMF agreement in April, when the new band system was introduced, allowing the exchange rate to fluctuate within its limits, that the crisis started. Milei promised that the peso would appreciate, which, in terms of the domestic dollar price, meant it should have moved towards the floor of the band. In reality, however, the exchange rate quickly moved to the ceiling, indicating a sharp depreciation of the peso instead of the promised appreciation.

The pressure on the peso increased, raising doubts about whether the current stabilisation plan, which seems highly dependent on both keeping the nominal exchange rate relatively stable and controlling wage pressures, is sustainable. Note that the economy remains in recession, largely due to the government’s fiscal austerity programme, leading to high unemployment and widespread poverty. Milei’s planned reforms—including labour and pension reforms—mirror earlier neo-liberal adjustments, reinforcing inequality and social strain, and indicate that wage pressures will remain subdued. This could have significant political consequences for the government and threaten social stability.

On the exchange rate front, Argentina’s recent stabilisation owes much to extra¬ordinary external support. In summer 2024, China renewed a currency swap line that helped Argentina meet IMF obligations, with Argentina even servicing IMF debt in yuan, an unprecedented arrangement. Further, in April 2025, the IMF approved a $20 billion loan package for Argentina, supplemented by a pledged $20 billion from the US Treasury, and the backing of financing deals with Wall Street investors, with some fuzzy guarantee from US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent. The US’s active role in supporting Argentina’s credit and exchange rate stability—actions unparalleled in recent regional history—has been des¬cribed by some as part of a new Monroe Doctrine and, according to others, a Trump Doctrine in the Western Hemisphere. [5]

This extraordinary backing stabilised Argentina’s country risk and currency pressures, helping Milei secure a victory in the midterm elections. Yet the very conditions that permitted this support—Argentina’s lack of reserves, persistent external vulnerability, and dependence on foreign financing—illustrate how tenuous its current stability remains.

Why Exchange Rate Depreciation Cannot Work

As noted, the dominant narrative suggests that the more recent run on the peso was triggered by the brief electoral victory of the Peronists in Buenos Aires Province in September 2025, ahead of the national elections in October. The argument is that fear of a return to populism and fiscal profligacy sparked speculation on the peso, which in turn prompted conditional support from the Trump administration. Money was expected to flow to Argentina if Milei’s party won; once the victory came, the pressure for depreciation intensified.

As noted, the argument equates depreciation with increased export competitiveness, but that does not reflect Argentina’s export structure. Argentina primarily exports commodities — soybeans, corn, oil and natural gas — whose global prices are not affected by Argentina’s exchange rate. A depreciated peso does not make these prices higher on international markets, and global demand constraints, such as slowing growth in China and the US, limit export expansion. Certainly, some industrial sectors might benefit marginally from a weaker peso, but these sectors are either small relative to Argentina’s overall export portfolio or part of complex regional production chains (for example, Mercosur automotive supply networks) where exchange rates matter less.

In contrast, large depreciation has direct inflationary effects by raising the peso prices of imported goods, fuelling speculation against the currency and reducing real incomes. The contractionary impact on domestic demand and imports might modestly improve the trade balance, but for the wrong reasons: declining domestic activity rather than export growth.

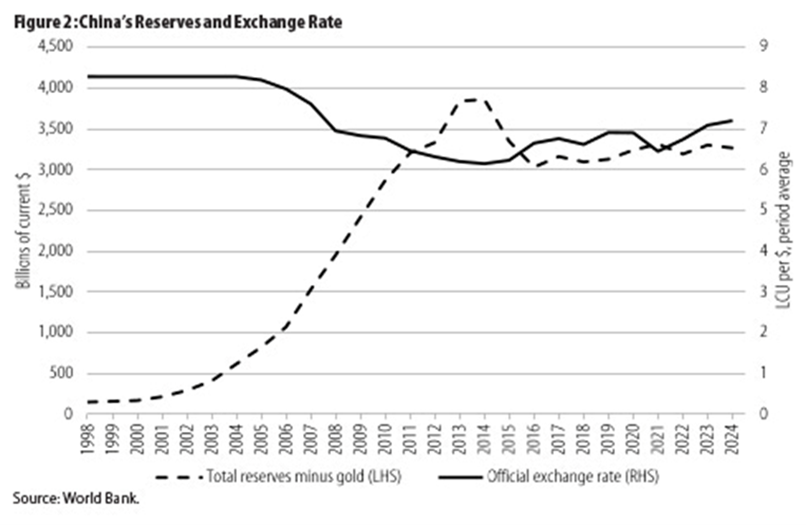

Moreover, efforts to have the central bank accumulate reserves through exchange rate flexibility would likely intensify speculation against the peso, further destabilising the currency and undermining confidence. Note that the accumulation of dollars by the central bank requires it to buy foreign currency and sell domestic currency, reinforcing tendencies for the currency to depreciate. Consider the case of China, often cited as an example of a country with both a competitive (depreciated) exchange rate—in fact, often accused of manipulating it—and dollar reserves of approximately $3.4 trillion at the People’s Bank of China. It is clear that the accumulation occurred while the nominal exchange rate was appreciating (Figure 2). Similar figures can be shown for almost any country that accumulated large foreign reserves in dollars.

In other words, the effort to accumulate reserves—something that Argentina sorely needs, no doubt—can only take place in an environment in which there is no speculation against the domestic currency and in which economic agents are willing to hold assets in domestic currency. That is hardly the case for Argentina.

Under these circumstances, the only way to prevent a large depreciation of the exchange rate—which under the current rules might occur with rising inflation associated with the rules for adjusting the exchange rate band—would be for the central bank to intervene to keep the nominal exchange rate under control.

It is important to note that we are not advocating a return to fixed exchange rates or Bretton Woods-style capital controls, since such frameworks are neither feasible nor attainable in the current global financial architecture. Maintaining stability requires very high interest rates to compensate for global reference rates, political risk, and expected depreciation. Milei’s government seems to recognise this and aims to hold the exchange rate within the band, but it has increasingly moved in the direction of a more flexible exchange rate arrangement. The very mechanisms it has instituted—exchange rate bands tied to inflation—risk creating self reinforcing depreciation and inflationary dynamics.

By definition, this means not accumulating reserves, since the central bank would have to sell dollars at the band established price. But in the absence of reserves, this requires the continuous support of the IMF and the US administration. The New Monroe Doctrine might save Milei for a while. It is highly dependent on US domestic politics. The Argentina package and the trade war with China have hurt Trump’s electoral base among agricultural exporters, particularly Iowa’s soybean producers, forcing him to provide a rescue plan.

Even if Milei manages to keep the exchange rate relatively stable and hence avoid the lure of a competitive exchange rate that might solve Argentina’s external problems, his position might be socially untenable.

His plan after his electoral victory in October is to push for the deregulation of labour markets and to maintain fiscal austerity. The hope is that this would bring market confidence and foreign direct investment flows that would both alleviate the external constraint and promote economic growth. This was the same promise made by all previous neoliberal experiments in Argentina, which have invariably failed (Vernengo 2025). We should expect these measures to deepen the recession and heighten social tensions. While they may alleviate some external pressures, they will do so at high social cost and without resolving Argentina’s underlying structural constraints.

In Conclusion

Argentina’s immediate priority must be nominal exchange rate stability to control inflation and support a gradual recovery in real wages, which are essential for domestic demand and sustainable growth. Argentina’s current economic strategy, increasingly premised on exchange rate adjustment as a panacea for external imbalance, rests on theoretical misconceptions and empirical misreads of how exchange rates interact with commodity dependence, global demand, and capital flows. True external sustainability for Argentina will not arise from finding the “right” exchange rate; it requires a coherent strategy that combines nominal stability, productive diversification, and policies that strengthen both domestic production and markets without increasing the pressure on external accounts, and without undermining social cohesion.

Under the shadow of an evolving geopolitical context—the so called Donroe Doctrine—Argentina’s dependence on external support further complicates prospects for autonomous economic policy. Unless structural reforms address the real sources of external vulnerability and foster inclusive growth, Argentina’s path forward will remain highly precarious.

Lead photo of Milei & Trump sourced via Wikimedia, link https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:President_Donald_Trump_participates_in_a_pull-aside_meeting_with_Javier_Milei,President_of_Argentina,_at_the_United_Nations_Headquarters(54823861698).jpg#file

Notes

[1] In its second year, in 2025, the Milei administration received a large, US-coordinated package of external support. In April 2025, the IMF approved a new Extended Fund Facility, alongside parallel commitments from the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank over several years. This was complemented by strong backing from the US administration, including contingent support through swap arrangements and other liquidity backstops intended to stabilise reserves and market expectations. Private banks were initially expected to play a larger role, but their participation was subsequently scaled back, leaving the overall effort heavily reliant on official financing. Taken together, these commitments that took the form of swaps, guarantees, and disbursement-conditional credit lines and only partly translated into immediate cash transfers, represent a US guarantee of Argentine credit. In some ways, this financial commitment to reduce country risk is the financial part of the Donroe Doctrine.

[2] On the notion of a conventional exchange rate, equivalent to Keynes’ conventional interest rate, see Vernengo (2001).

[3] For detailed historical accounts prior to Macri, see Öncü (2024) and Vernengo (2025).

[4] For a discussion of the Argentine situation after the two renegotiations of foreign debt stemming from the 2002 default, but before the payments to the “vulture funds,” see Vernengo (2014).

[5] As the National Security Strategy of the United States (November 2025) states, they “will assert and enforce a ‘Trump Corollary’ to the Monroe Doctrine,” although whether this is a “corollary” or a new doctrine remains hotly debated, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/2025-National-Security-Strategy.pdf

References

Amico, Fabián, Franklin Serrano and Matías Vernengo (2022): “Cómo evitar el bimonetarismo y el monetarismo,” Le Monde Diplomatique, https://www.eldiplo.org/notas-web/como-evitar-el-bimonetarismo-y-el-monetarismo/.

Öncü, T Sabri (2014a): “A Sovereign Debt Story: Republic of Argentina vs NML Capital,” Economic & Political Weekly, Vol 49, No 20, pp 10–11.

— (2014b): “Cry for Me Argentina,” Economic & Political Weekly, Vol 49, No 42, pp 10–11.

— (2024): “From Chile in 1973 to Argentina and Türkiye in 2023: Economic Genocide Continues,” Economic & Political Weekly, Vol 59, No 19, pp 10–13.

Vernengo, Matías (2001): “Foreign Exchange, Interest and Prices,” Credit, Interest Rates and the Open Economy, Louis-Philippe Rochon and Matías Vernengo (eds), Aldershot: Edward Elgar.

Vernengo, Matías (2014): “Argentina, Vulture Funds, and the American Justice System,” Challenge, November–December, Vol 57, No 6, pp 46–55.

Vernengo, Matías (2025): “Make Argentina Crash Again: On Milei’s Neoliberal Experiment,” American Prospect, https://prospect.org/2025/11/24/argentina-bailout-javier-milei-trump-neoliberal/.

Vilches, Jorge and T Sabri Öncü (2015): “Did Argentina Default?” Economic & Political Weekly, Vol 50, No 4, pp 25–27.