Chinese workers in Guangzhou clearing the sludge. Photo by Jeremy Smith (PRIME)

The year 2015 began with the Chancellor, George Osborne ‘welcoming’ the news that inflation had fallen in December 2014 to 0.5% – more than 1% below the official target. The FT declared that “this is almost certainly ‘good deflation’“.

In his subsequent letter to the Chancellor the governor of the Bank of England attributed the fall to “unusually low contributions from movements in energy, food and other goods prices.” In other words he described the symptoms – falling prices – and neglected to analyse or explain the cause of such falls. Understanding the cause of falling energy, food and goods prices is fundamental to effective policy-making and to decision-making by investors. So by simply offering descriptions of events, the Bank of England – guardian of the nation’s finances – does society no favours.

In our view the cause of deflationary pressures lies with the ongoing Global Financial Crisis (GFC), which has not as yet been resolved. On the contrary the economic model that fostered the crisis remains intact, with only some tinkering at the margins of the banking system. As a result the GFC continues, rolling around from the core (the Anglo-American economies) to first the Eurozone, and now hitting emerging markets, including China. The GFC, as we now know, was caused by the bursting of excessive and unpayable private debt bubbles: bubbles that were punctured from 2006 onwards by high real rates of interest. (Think of high rates as daggers pointed at, for example, a bubble of sub-prime debt).

Unaddressed legacy of the crisis

While central bankers bailed out the private banking system, private corporate and household debtors were not so fortunate. The ongoing and unaddressed legacy of the Global Financial Crisis is therefore the global overhang of private corporate and household debt; an overhang that coupled with repressed wages and incomes in turn depresses demand for goods and services. The McKinsey Global Institute has shown that private and public debt continued to balloon after the 2007-9 meltdown, and that there has not been much deleveraging of that debt. By February 2015, global debt had grown by $57 trillion, raising the ratio of debt to GDP by 17 percentage points.

Governments continue to leave the management of the private debt overhang to “the market”. This has meant that the private debt crisis remains unresolved because market players and in particular bankers in what the BIS describes (p.26) as “the broken banking system” fear losses from defaults. As a result precious little is done to re-structure or write off unpayable private debts. Instead bankers “extend and pretend” and offer debtors more credit with which to pay down existing debts, thus inflating private debt bubbles across the world.

At the same time, the economic consequences of misguided austerity policies applied in both the US and then the UK and the Eurozone, both dampened demand in these economies, and led to a rise in public debt, as unemployment remains stubbornly high across the world, and repressed wages and incomes lag behind in real terms, causing government tax revenues to slump.

The private debt overhang coupled with austerity, falling incomes and falling demand continue to dog western economies. And while the US Federal Reserve’s QE programme acted for several years as a form of “life support” for asset markets, the removal of that life support in October, 2014 worsened weakening demand in the world’s biggest economy, the US and elsewhere.

Global weaknesses

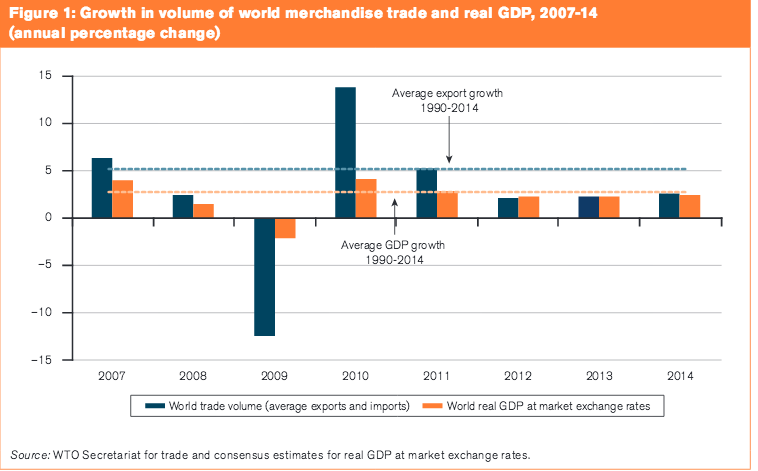

The weakness of US and other OECD economies is reflected in world trade data. As the WTO points out in its 2015 World Trade Report, trade growth since 2012 has been at “the slowest rate on record for a three-year period.” “China”, as George Magnus explains in Prospect magazine “is, after all, the world’s biggest trading nation, and accounts for about 13.5-16.5 per cent of world GDP.” The very slow rate of recovery from the GFC in the world’s biggest trading markets has therefore been damaging for the still export-oriented Chinese economy, resulting in the build-up of gluts in vehicles, rubber tyres, steel, coal and grain – to name but a few of the commodities and goods produced by China.

If this were not all bad enough, China’s wholesale adoption of the western liberal finance economic model has led to a rise in unsustainable private debt both in China and in other “emerging markets”.

Guangzhou finance centre, photo by Jeremy Smith, PRIME

These private debts increasingly act as a drag on economic activity in those markets.

However it is the global overhang of private debt and wage repression in western economies coupled with weakening demand in OECD economies, including the US, that has in turn led to the build-up of gluts in markets that produce the world’s energy, food and goods – including China. Which is why it is quite wrong to blame China and emerging markets for global weakness and deflationary pressures.

Victim not perpetrator

In this sense the debate about today’s volatility is reminiscent of the pre-2007 crisis debate in the US when, as now, China was blamed for the rise in global imbalances and in particular for the US’s large and rising current account deficits. In reality it was the reverse. The US’s embrace of an economic model based on unfettered movements in trade and finance and its exploitation of the dollar’s role as global reserve currency fed US corporate and household appetites for apparently insatiable mass borrowing and consumption. In a world of ‘liberalised’ globalized trade and finance the US appetite for cheap goods and services was met by China and led naturally to the build-up of surpluses as Chinese exporters fed the unquenchable US demand for such goods and services.

Once again, China is a victim of the global imbalances caused by the dominant western economic model – not the perpetrator of those imbalances.