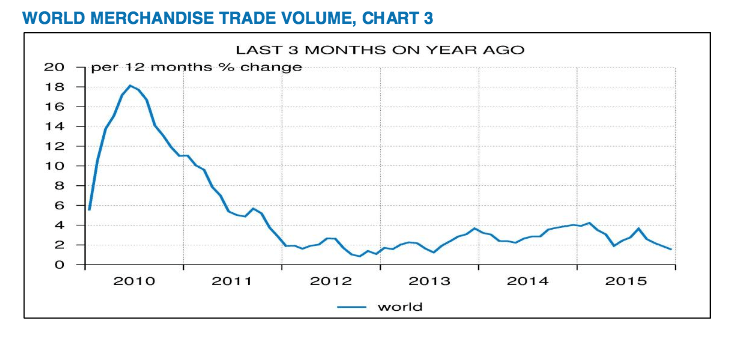

This slow-down in trade was then exacerbated by the October, 2013 decision of the US’s Federal Reserve to end “life support” for the US finance sector and the wider economy, and to “taper” its purchase of assets (bond-buying) under its programme of Quantitative Easing. This led as expected, to a further weakening of the US economy, which in turn lowered demand for commodities from emerging markets, most notably, China.

The Fed’s taper began in December 2013. Its decision was followed almost immediately by a steep fall in emerging market currencies and stock markets in mid-January, 2014. These in turn were followed by dramatic and ongoing falls in commodity prices, including oil. The ending of ‘life support’ led to a fall in US and then OECD-wide demand for goods and services from these emerging markets. A consequence was the build-up of gluts of steel, cement, autos, rubber and other goods in China and other emerging markets. These gluts in turn deflated prices at a global level, and led to turmoil and growing trade imbalances in emerging markets. Policy-makers like the UK Chancellor, and commentators in for example, the Financial Times were slow to react to the worldwide fall in prices, attributing the falls to the oil price alone, and calling the phenomenon “good deflation.”

As “deflationary tides (lap) at the shores of countries around the world” [4] members of the economic establishment are belatedly waking up to the huge threat posed by this relatively unknown, and widely misunderstood phenomenon.

Deflationary policies gradually, but inexorably increase the value of money (credit or debt) above the present value of goods and services – which is why they are favoured by the financial services sector. As Keynes once famously argued (in his Tract on Monetary Reform (1923)):

“Deflation, as we have already seen, involves a transference of wealth from the rest of the community to the rentier class and to all holders of titles to money; just as inflation involves the opposite. In particular it involves a transference from all borrowers, that is to say from traders, manufacturers, and farmers to lenders, from the active to the inactive.”

In some parts of the financial establishment complacency has now been replaced by scarcely contained panic, as expressed for example by the Washington-based Institute for International Finance – the elite club for private bankers:

“Vulnerabilities make the global economy highly fragile, susceptible to being tipped into synchronized downturn.” [5]

The OECD, the Economist, the Financial Times, the IMF and other cheerleaders for monetary radicalism and fiscal consolidation have recently made dramatic U-turns and expressed visible alarm at the threat posed by global deflationary pressures, high levels of private debt (including in China) weak economic growth, the risk of banking failures (as the cost of debt and therefore default risks rise relative to the deflation of prices and incomes); and of the possibility of renewed financial crises and a “synchronised downturn”.

The IMF argues [6]:

“near-term fiscal policy should be more supportive where appropriate and provided there is fiscal space, especially through investment that boosts both the demand and the supply potential of the economy.” At the same time the global financial and economic establishment – as represented by the IMF, the OECD and even the Economist – belatedly acknowledge that central bankers have exhausted the monetary policy tools (or “ammo”) at their disposal.

However, G20 finance ministers at their recent Summit in Hangzhou, China, were far less concerned. Indeed they allowed the UK Chancellor to hijack their final statement with a reference to Britain’s domestic problems over a forthcoming referendum. For those who could find it buried under the Brexit news coverage, the G20 communiqué was upbeat about the economic outlook, and divided over the need for co-ordination or collective action. They recognised the “challenges” facing the global economy, but nevertheless

“expect activity to continue to expand at a moderate pace in most advanced economies, (while) growth in key emerging market economies remains strong.”

Such shrug-of-the-shoulders complacency is worrying, given the divisions that exist at global level. As Bloomberg reported:

“With the U.K. mulling spending cuts, Japan planning a sales tax increase, Germany’s finance minister warning debt-funded growth just leads to “zombifying” economies, and the U.S. constrained by a lame duck president and Republican-controlled Congress, it may fall to China to ratchet up the fiscal firepower.” (Bloomberg, 27 February, 2016.)

However China faces big challenges too. It is a nation with large numbers of poor people, and with levels of private debt that exceed US debt levels as a share of GDP. China cannot therefore be expected – to once again – singled-handedly drive the recovery of much richer, austerity-fixated OECD economies.

So while the international club of bankers is worried that “vulnerabilities make the global economy highly fragile, and susceptible to being tipped into synchronized downturn” [7] – G20 finance ministers refused to bury both their differences, and their obsession with austerity – to synchronise their response to this “highly fragile” global economy.

Their confidence in austerity is surely misplaced. For as Mark Carney, governor of the Bank of England noted recently, the British Chancellor expects “the largest fiscal consolidation in the OECD” to lead to a decline in the structural deficit of around 1 percentage point a year over the next four years. This after the deficit has only fallen by 1/3 of a percentage point on average over the last three years – despite a massive fire sale of UK taxpayer-owned assets.

So, expect very little global leadership or co-ordination from our elected politicians. They remain captured by contractionary, deflationary economic theory and policies; policies which serve the interests of the rentier – the titleholders of money. Policies which threaten to tip the global economy once more into a “synchronised downturn”.

Footnotes:

[1] The Turn of the Year: Mark Carney, governor of the Bank of England, Peston Lecture, Queen Mary University, London, 19 January, 2016.

[2] OECD (2011), “Fiscal consolidation: targets, plans and measures”, OECD Journal on Budgeting, Vol. 11/2

[3] Trade and Development Report, UNCTAD, 2015, p. 6.

[4] To quote Vikram Mansharamani, a lecturer at Yale University on CNBC, 3 March, 2016. I see bubbles bursting everywhere.

[5] Institute of International Finance (IIF), Washington. 21Feb, 2016. http://ow.ly/YwmHL

[6] Group of Twenty IMF Note — Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors’ Meetings

IMF Note on Global Prospects and Policy Challenges, February 26-27, 2016.

[7] Institute of International Finance (IIF), Washington. 21Feb, 2016. http://ow.ly/YwmHL