Nature of the Health Crisis

The current health crisis has similarities to the Great Recession of 2008-2009, though fundamentally different. The crisis ten years ago resulted from collapse of financial institutions, a purely human-made disaster whose solution should have been obvious. The financial collapse provoked a severe contraction in aggregate demand in household spending and business investment. The demand contraction led to under-utilisation in most sectors, which a fiscal stimulus would have resolved — inadequate demand, idle production and workers, correctable by the public budget replacing private demand with public demand.

The current economic contraction represents a production crisis, a spreading contraction in output as people self-isolate and the government orders workplace and shop closures. The essential impact on the economy is the restriction of economic activity leading to a sharp decline in incomes and demand, the opposite causality of 2008-2009. Some, including Paul Krugman, have called this a “supply side” crisis. I avoid that terminology because of its unfortunate association with neoliberal ideology, the dogma that deregulation, “supply side reforms”, would stimulate production through increased “efficiency” generated by market competition.

Policy response

A production crisis implies that the policy response must include and go beyond income replacement schemes. The UK government proposed and will implement legislation to replace 80% of the earnings of redundant employees. Payment of a basic income to all citizens represents an alternative viewed by many as more effective.

Compensating for loss of household income provides a necessary but not sufficient response to the production crisis. People not working by definition means production not realised. Production of essential goods such as food and other household necessities will continue as far as is possible. Three sources of disruption immediately come to mind:

spread of illness might create labour shortages in some sectors;

transport and delivery systems could reach capacity constraints, and

disruption of international trade flows could require greater reliance on national supply.

An increasing number of experts has pointed out that the globalisation created long supply chains render the UK production and supply system vulnerable to disruption. The cost-cutting practice of minimising inventories is also an important source of vulnerability though less fundamental. At the moment domestic production accounts for slightly over half the food consumed by UK households.

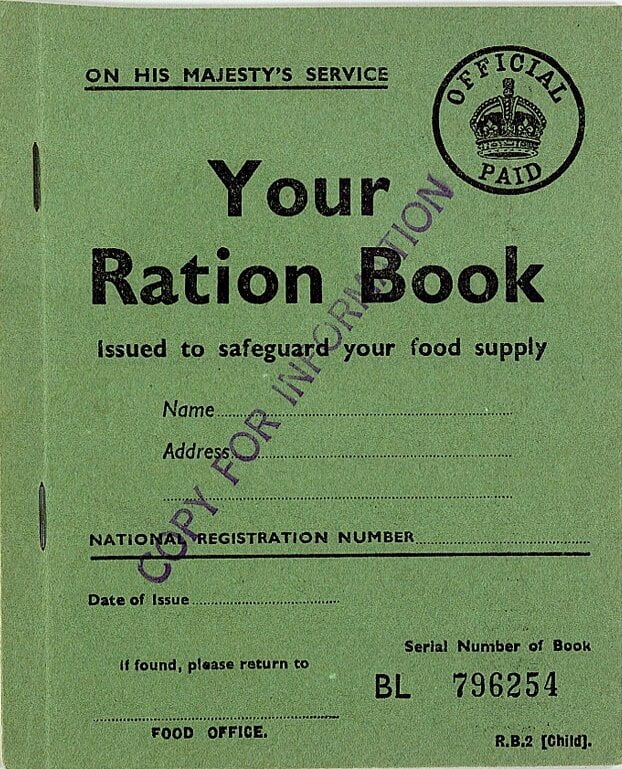

The three sources of disruption to the supply of essential production lead to obvious policy steps. First, quantity rationing of essential productions requires urgent consideration and planning. I am careful to use the modifier “quantity” because all market economies enforce rationing — households and businesses ration purchases on the basis of price and income. The UK government enforced quantity rationing by use of ration books during and after World War II.

Second, rationing implies price controls. In the United States price and profit controls, administered by the Office of Price Administration, supported quantity rationing from the outset in 1941. Prevention of excessive profits, “war profiteering”, was a central part of price administration. Harry Truman obtained the prominence to become Franklin Roosevelt’s vice president in 1945 by his Senate hearings on war profiteering. In Britain quantity rationing continued well after the end of WW II, formally ending in July 1954.

Third, the government should initiate a broad “industrial policy” pointed at increasing domestic production of essential household products and medical equipment. This programme would include credit directed through commercial banks, price subsidies and price guarantees. For agriculture adoption of a variant of pre-EU policy could enhance national production. Stated briefly, the EU Common Agricultural Policy, which the British government joined when it became a member, involved measures to protect agricultural production by holding prices high and absorbing surpluses through official purchases.

The UK’s pre-1973 agricultural support system kept prices low. The government set a guarantee price, farmers sold on the open market, and were paid the difference between the support price and their market price. The result was low consumer prices as farmers produced up to their limits with no surpluses for the government to absorb.

To be concrete, the UK government could create a Basic Necessities Control Board, with at least three parts, offices of 1) price regulation, 2) production management, and 3) labour supply. The latter would avoid the suggestion to import 90.000 agricultural workers from Central and Eastern Europe.

This latter proposal is extremely unwise — during a pandemic importing people from countries desperately struggling to contain the spread of Covid-19. It indicates a lack of common sense. The obvious solution to shortages of agricultural labour — and workers in essential sectors in general — is decent pay and adequate housing for the coming months and training schemes for the longer term. The same policy would act to overcome shortages of health workers. Self-congratulatory references to the large number of non-UK NHS staff fail to mention that active overseas recruitment reflected an attempt to attract cheap labour to the under-funded NHS, with the result of draining essential skilled workers from poor countries.

Longer term responses

Central to my proposal is whether it would represent a transitory crisis response or a fundamental change in policy for the long term. Changes clearly advantageous for the long term are

domestic training of health workers (of residents of all national origins) rather than importing cheap labour from low-income countries,

replacement of the EU agricultural support programme with a pre-1973 type system now that we are out of the Union, and

legislation to facilitate a Basic Necessities Control Board that the government could initiate in an emergency.

Two major policy changes may seem discretionary but in my view highly desirable. Price control or at least monitoring of basic commodities should become permanent practice, as should public provision of a small number of those necessities, for example heating, electricity and transport.

The recent macroeconomic stimulus and income support programme may mitigate the gathering recession. The government should also address the inevitable production consequence of a lockdown, by purposeful intervention in commodity and service markets.

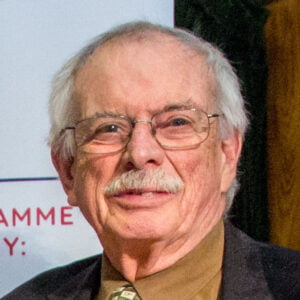

Professor John Weeks is Emeritus Professor, SOAS, London. His most recent book is “The Debt Delusion” (Polity). You can follow him on Twitter @johnweeks41.

2 responses

on your conclusions… his conclusions:

why? does it matter where they come from? we have a demographic issue which is more important than nationality of workers. if the government paid doctors properly there would be more of them here anyway, like in the US

"The UK’s pre-1973 agricultural support system kept prices low. The government set a guarantee price, farmers sold on the open market, and were paid the difference between the support price and their market price. The result was low consumer prices as farmers produced up to their limits with no surpluses for the government to absorb." this is true and critics of the CAP are always talking about wastage, pollution, etc. but what will happen when there is a black swan in food production and there isn’t enough to eat? then what are the people who want more efficient food production and distribution gonna say? same situation as has happened with underfunded medical programmes in the virus situation. The CAP policies have their purposes, albeit i am not an expert of it.

there has been no supply / production shortage, other than loo roll over a couple of days due to the shock outweighing of distribution from production centres. this wont happen again now that people have confidence in the system. likewise, labour supply is there if it is necessary, even just by volunteers, as the NHS volunteers have shown. Price regulation? supermarkets are in intense price wars constantly – this is a non starter.

Overall, the guy seems to be a brexiteer in his conclusions and there are some alllusions to a philosophy of "we can do it better on our own"…. bollocks. He is making unnecessary (and in my opinion, minoorly racist) policy suggestions to problems we dont have and not addressing clear policy shortcomings we do have.

John… in response

most sectors are suffering a dramatic oversupply of labour. unemployment is probably going to reach record levels – how can this be labour supply shortage? perhaps in some specialist bottlenecks, but certainly not broadly. people are volunteering in their 100s of thousands for the NHS where they are needed!!!

obviously no one is going anywhere or using transport, hence transport systems are operating well, well below their capacity, which is usually stretched. Again, no idea how this is a threat. Also, transportation costs are through the floor after oil has tanked. In terms of delivery systems, it is obvious that this has been impacted for food. Luckily, it is clear that the social distancing policy has allowed much normal essential distribution to occur. In the longer run, I think amazon (and therefore other businesses) is well placed to use robotic systems to ensure that this is not a threat, even if a future pandemic required even less social interaction. moreover, people might not be so concerned in future episodes as the system has been shown to be robust.

Perhaps in the longer run some businesses might struggle and if these go under gaps could appear in some supply chains. Nevertheless, the funding measures taken by governments will act strongly against this by increasing credit availability and lowering borrowing costs. Furthermore, big companies are very wary of issues in their supply chains and will act to stabilise quickly.

In terms of food, the supply chains are very robust and shock dispersion processes are extremely well designed (i.e. under the CAP). It is again clear that some speciality items may be less available in time, but there are significant stock piles for most stuff I believe. Over the longer term, it is clear that some western governments (Trump, Brexit) are trending towards protectionism and more local production. This may be exacerbated by the pandemic. However, the opposite is true in Asia, i.e. the ASEAN – China FTA in 2019.

More broadly, I was initially of the opinion that this could be inflationary because of the supply shock. However, businesses are widely able to use technology to continue to operate essential functions and this should ensure these continue – i.e. food. Meanwhile, the housing market is shut, there is no transportation, energy costs are through the floor and no-one is doing anything. Under these circumstances I am now trending more towards deflation. People arent gonna shit more just cos there is a loo roll shortage – in fact, they are probably gonna do less exercise, eat less and shit less, meaning we have too much loo roll.